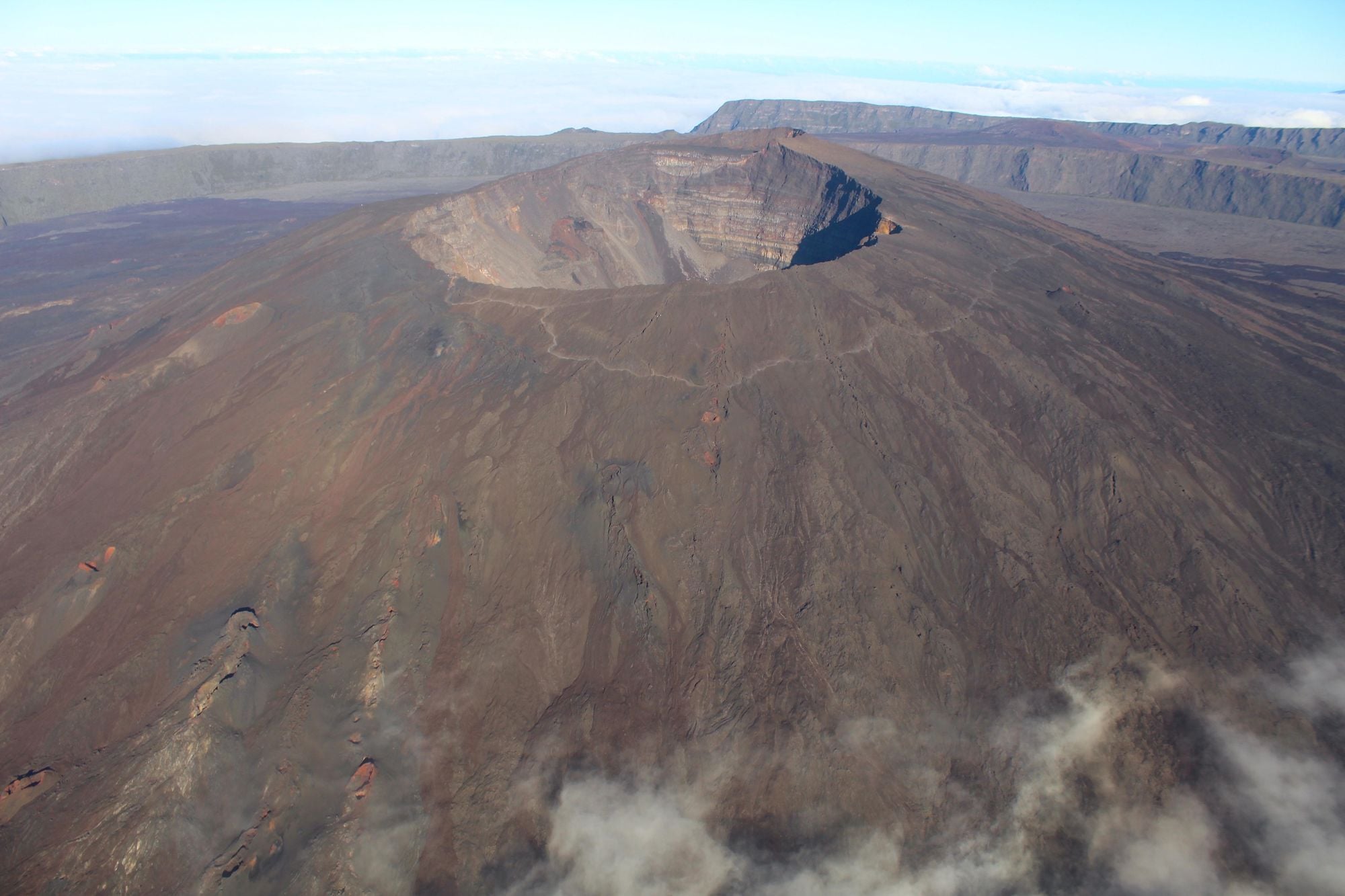

I travelled to Réunion Island with a dream of the place; of this farflung island, born when the shield volcano Piton des Neiges erupted from the Indian Ocean three million years ago, 440 miles (708km) east of Madagascar. That island is now French department 974, where sharks circle, mountainous cirques dominate the interior and Piton de la Fournaise - the 'Peak of the Furnace', one of the most active volcanoes in the world - bubbles and erupts every year.

Almost all of the cities on Réunion Island, including the capital of Saint-Denis, are on the coast. “We live in between the sharks and the volcanoes,” as Christophe, a Réunionese local I met on the 12-hour flight from Paris had put it.

Réunion is not a place quick to reveal its secrets.

If foreigners have heard of Réunion at all, it's often because of those sharks.

Between 2011 and 2016, this tiny island accounted for 16% (7 out of 43) of the world’s fatal shark attacks. There has not been a fatality from a shark attack here since 2019. Nonetheless, swimming and surfing remains prohibited on large stretches of the coast, though it must be said that surfers can often be spotted catching perfect, curving waves in sight of the shark-clad warning signs.

Regardless, the interior, not the coast is the main draw of Réunion, where the French word for wild, sauvage, feels more fitting than any English equivalent.

There are three dramatic cirques here. They are deep, rugged valleys, lined by huge, spiky ridgelines, forged by the collapse and erosion of Piton des Neiges over millenia. At 3,090m (10,137ft), the volcano is the highest point in the Indian Ocean, and it dominates the view from much of the island. The slopes career down from a sharp, central ridge. From afar, the mountain itself looks like a behemoth bull shark, waiting to break out the rock and escape into the water.

Piton des Neiges last erupted 12,000 years ago. Piton de la Fournaise is active.

The fact that locals say it’s currently in a quiet period, having not erupted since August 2023, is a clue to how often 'the furnace' usually lets loose.

Réunion is an island which is only 970 square miles (2,512 km²) in size, but the ferocity of the landscape means there are over 150 microclimates. Often clouds engulf the peaks above the cirques or hide the valleys below them.

Réunion is not a place quick to reveal its secrets. To discover them, you need to give time, sweat and attention to this spellbinding island.

Of Water, Rock and Fire

Being French, Réunion has the benefit of having three Grande Randonnée (GR) routes - long-distance walking paths which are well-maintained and waymarked. We followed the GR-R2, which crosses the island from Mafate cirque in the north, over 62 miles (100km) to Piton de la Fournaise in the south.

On the trek, my wild dream of Réunion became an electrifying, exquisite reality.

Mountains, triangular as though drawn by a child, stacked in layers, and waterfalls that plummet down them...

Our journey began in Saint-Denis, the noisy capital of Réunion where French Colonial architecture mixes with Creole colour and avocados the size of a human head are sold on market stalls alongside fresh vanilla pods. By the coast, locals play boules and cards under palm trees, drinking the omnipresent local beer ‘Dodo’, named after the extinct animal which once lived in this region (if not definitely on this island). There is an actual dodo skeleton in the natural history museum nearby. Walk the streets and you’ll see the number 974, the French department code for the island, graffitied on walls. And the flag of Réunion - beams of yellow sunlight surrounding a red mountain, on a blue sky - flying.

The city of Saint-Denis slopes slowly up from the coast to the mountains.

We entered Mafate via Saint-Paul, a city further around the coast. Mafate is the only one of the three cirques here (the others being Salazie and Cilaos) not accessible by road. Around 800 people live in the remote îlets of Mafate. These are islets surrounded not by water but dense greenery, hidden beneath mountain ridges. Supplies are choppered into them by helicopters, which fly low through the tight canyon walls like metal dragonflies, and buzz over cirque walls.

The only way for the everyman to explore Mafate is on foot, and the topography is like spiking heart rate monitor. Up. Down. Up. Down. Steep up. Steep down.

The path is well kept, but everything around it is truly wild; left to itself. We pass pink poinsettia flowers, wild pineapples and trumpet-shaped brugmansia.

When the switchback staircases on these cirque walls are exposed to the tropical sun, the hiking is extraordinarily tough, but you're never far from some jaw-dropping panorama; of mountains, triangular as though drawn by a child, stacked in layers, or waterfalls that plummet down to rivers on the valley floor.

An arrival at a remote gîte is (unfortunately) usually only earned through a final demanding climb. But I found these mountain bunkhouses tended to appear out of the mist, as though by magic, when you simply couldn’t walk any more.

The history of these îlets is fascinating. Though Réunion had no native inhabitants before the 16th-century, the French brought slaves from Africa, India and Madagascar when they settled here, and many of these îlets were first formed as ‘maroons’ by escaped slaves.

Local legend has it these tropicbirds were once mermaids, cursed by an evil genie. They now fly to sea in search of their old home; Atlantis.

In L'Îlet des Orangers, a village halfway up a mountain wall (which seemed impossible to reach when viewed from the other side of the valley), we plucked oranges and bananas from trees and played pool on a slanted table. In the distance, white-tailed tropicbirds, which nest in the cliffs but fish at the sea, are a reminder of how close the ocean still is, regardless of how far away it may feel.

Tropicbirds are easily identifiable by their forked tail feathers, which look like ribbons in flight. Local legend has it these tropicbirds were once mermaids, cursed by an evil genie. They now fly to sea in search of their old home; Atlantis.

The City in the Cirque

I dreamt of mermaids that night, in a cosy four-bed dorm, where we regained our strength after a tough first day of hiking. My memory of leaving Mafate after three days is of roots, rocks, ferocious uphill and, when it was done, of the town of Cilaos, appearing in the distance, dominated by mountain walls on every side.

Cilaos is an utterly fantastical place for a commune; a town so unlikely it should really only exist in stories. It's home to 5,000 people, to wide roads, football pitches, to street art and sandwich shops which blare music in Réunion Creole.

We stayed in Cilaos for two nights, using our rest day to walk down to Bras Rouge waterfall, a gorge with a famous rock feature known as ‘The Cathedral’. It looks like nature's best attempt at sculpting in Pablo Picasso's cubist style, and shows what can emerge when water runs continually down hard, polished lava.

From Cilaos, Piton des Neiges, the founding father of this island, beckoned.

Accompanied by local stonechats and paradise flycatchers (a bright red and blue bird) we hiked relentlessly uphill for hours until Cilaos, and the clouds, were far below, and the town was framed in the distance by the peaks and clouds.

Most hikers break the ascent of Piton des Neiges down into two days, stopping at the refuge beneath the summit (called Le refuge de la Caverne Dufour), and then rising at 3am to climb up for sunrise. With the weather against us the next day, we adapted that plan, arriving at the refuge and ditching our heavy backpacks, then heading up to the summit to catch the sunset over Réunion instead.

The grey gravel rock turned to crumbly, oxidised red as we reached the higher echelons of the volcano. It broke into scree in sections. Then came the summit.

Beneath us, the pyramid peaks of Mafate poked out of the clouds. Piton de la Fournaise was visible in the fading light southwest. In the breaks in the clouds, it was tough to tell where the sky stopped and the Indian Ocean began. And in closer proximity, golden light bathed the volcanic rocks of this mighty volcano, creating a dreamscape of ridgelines rising out of cloud inversions; a mountain sanctuary, lined by steep cliffs. Some high points can be anti-climatic after a tough hike; this one felt powerful - a showcase of the extremity of Réunion.

I did not sleep a wink in our nine-bed dormitory that night, but a full bowl of coffee and a programme of rocky, rooty downhill allowed me to stumble on through the landscape the next day, with views over the forest of Bébour.

We soon left the national park and emerged out to grazing cows, horses and an altogether gentler landscape.

We looked down into the heart of this volcano, the crater of which is slowly filling up with each eruption. Beyond in the distance, the ocean glistened.

If you ever find yourself in the town of Bourg-Marat, I highly recommend La Cité du Volcan, a terrific museum exploring volcanic lore and science. Interactive exhibits explain how Piton des Neiges formed Réunion, while television footage and news clippings show the damage that Piton de la Fournaise can do when it erupts. In 2007, the lava flowed to the ocean, engulfing buildings and roads along the way. It is a fascinating insight into the formative power of fire and the perfect preparation for what followed on our hike - a trip through the Plain des Sables, a volcanic moonscape - and the approach to Piton de la Fournaise.

The Ground Beneath Our Feet

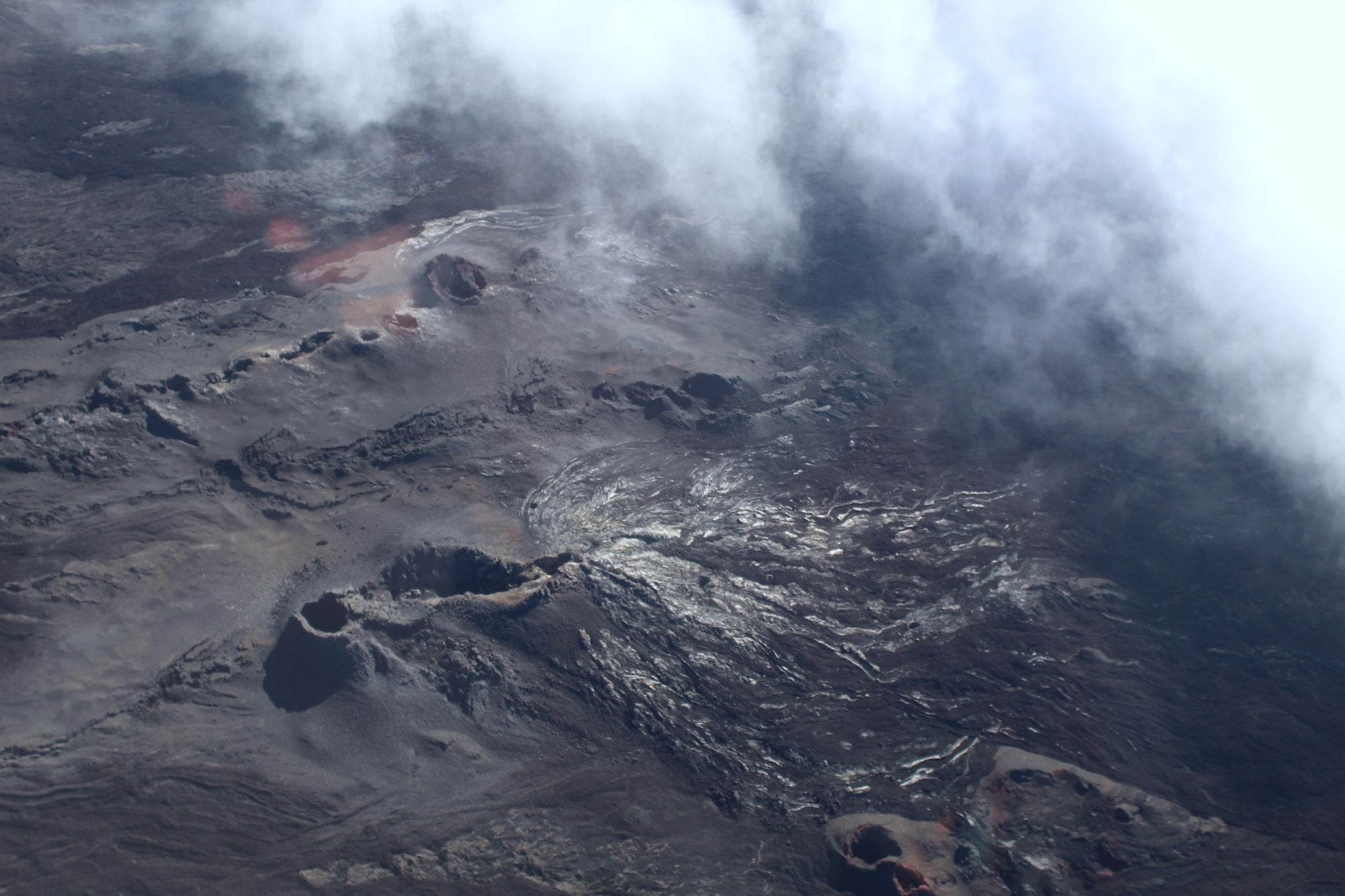

The floor is, quite literally, lava in this part of Réunion - crumbled, black igneous rocks and older, smoother dried lava flows. The rope lava, where running magma has stopped and solidified, looks like a rug which needs shaken out.

The clouds crawled over a cliff nearby as we walked through the Plain des Sables, giving the impression that steam was coming off the landscape.

We spent the night at the newly-opened Gîte du Volcan, which was by a long-shot the most modern and stylish gîte we stayed in (though what the others lacked in elegance, they make up for in personality). The 100-capacity bunkhouse is split across three buildings which, from above, are designed to look like curving lava.

Our alarm clocks went early the next morning, and at 6am we walked on to Piton de la Fournaise while the sun was rising. On approach, what emerged was a geological wonderland. We descended into the sprawling Enclos Fouqué caldera, a playground of dried magma, some of which has sat for millenia, some of which is as recently-formed as 2023. You can see the difference between the ages of rock in the darkness of the newer forms, and you can easily trace the paths these rock fields once flowed - the dark black lava fields stretching out in the caldera.

This volcano - unlike the rest of the GR-R2 - is very much on the Réunion tourist trail. You can drive to a car park near the volcano, so in the afternoon, it gets busy. But this was morning, and besides, our guide led us away from the marked, white route to the summit and instead took us directly up the side of the volcano.

We detoured briefly down into some magma chambers inside the volcano, where head torches were required, and then walked up to the silent, magnificent rim. We looked down into the heart of this volcano, the crater of which is slowly filling up with each eruption. Beyond in the distance, the ocean glistened.

It is, beyond all else, this contrast and intensity of Réunion that is so remarkable.

This is an island where you can feel like you are deep in the Amazon rainforest one moment; like you're walking through the shrubland of Tasmania, or the forests of Japan the next, then suddenly, like you've arrived in the Caribbean.

It feels alive - still moving, shifting, rejecting the idea that land must have a definitive, final form.

In the case of the volcanic southeast, it feels like you’re hiking on another planet - and yet all of these landscapes exist just a few miles away from one another. Each, while so visually distinct, is intrinsically connected. The crumbling, eroding lava is ultimately responsible for the mosaic green fertility of Mafate. The oceans that surround Réunion, where dolphins, whales and sharks swim, are the reason why tropicbirds fly over your head while you're in the forests.

Pull at one facet of Réunion - this stunning showcase of world-building - and you see that every single bit of nature is connected to the next.

We end our hike. And back on the touristy west coast of Saint-Gilles, we rest up and snorkel, watching tropical fish and turtles swim around underwater lava.

Réunion, more than any other environment I've experienced, feels alive - still moving, shifting, rejecting the idea that land must have a definitive, final form.

This island is a vivid reminder that we do not live on a settled planet which has already concluded some drawn-out journey. Our continents are still shifting and our world is still changing - sometimes slowly, with the dropping of a leaf or the shuffling of a seed. Other times, with the burning intensity of flowing lava.

Inspired? Trek the Grand Traverse of Reunion Island with us in 2026!