On 15 January 2021 a team of Sherpas celebrated one of the most coveted achievements in mountaineering: becoming the first people to ascend K2 in winter. It is the last of the world's 14 peaks over 8,000m high to be climbed in the season, and their effort was proof that "collaboration, teamwork and a positive mental attitude can push limits” of what is possible, said expedition member, former Gurkha and UK special forces member Nirmal Purja.

That same sense of teamwork and collaboration was not quite so in check on the infamous first ascent of K2, the second highest mountain in the world, by the Italians Achille Compagnoni and Lino Lacedelli - way back on 31 July 1954.

Remember if you succeed in scaling the peak - as I am confident you will - the entire world will hail you as champions of your race and your fame will endure throughout your lives and long after you're dead.

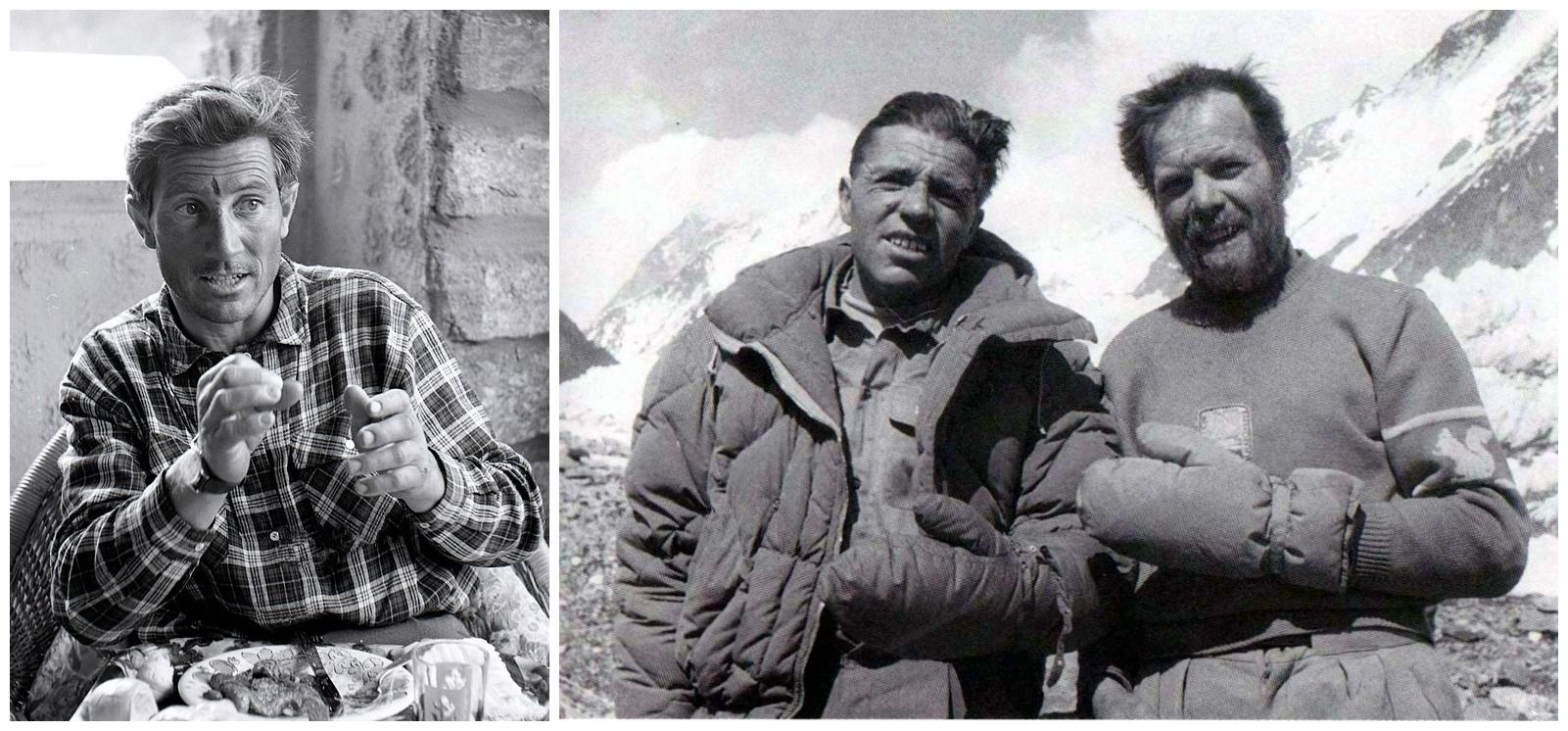

There was never any debate over whether Compagnoni and Lacedelli summitted the mountain - photographic evidence put that beyond doubt - but there was controversy for decades over how Hunza porter Amir Mehdi and young climber Walter Bonatti ended up having to bivouac out in the open, without a tent or even a sleeping bag, at an altitude of 8100m.

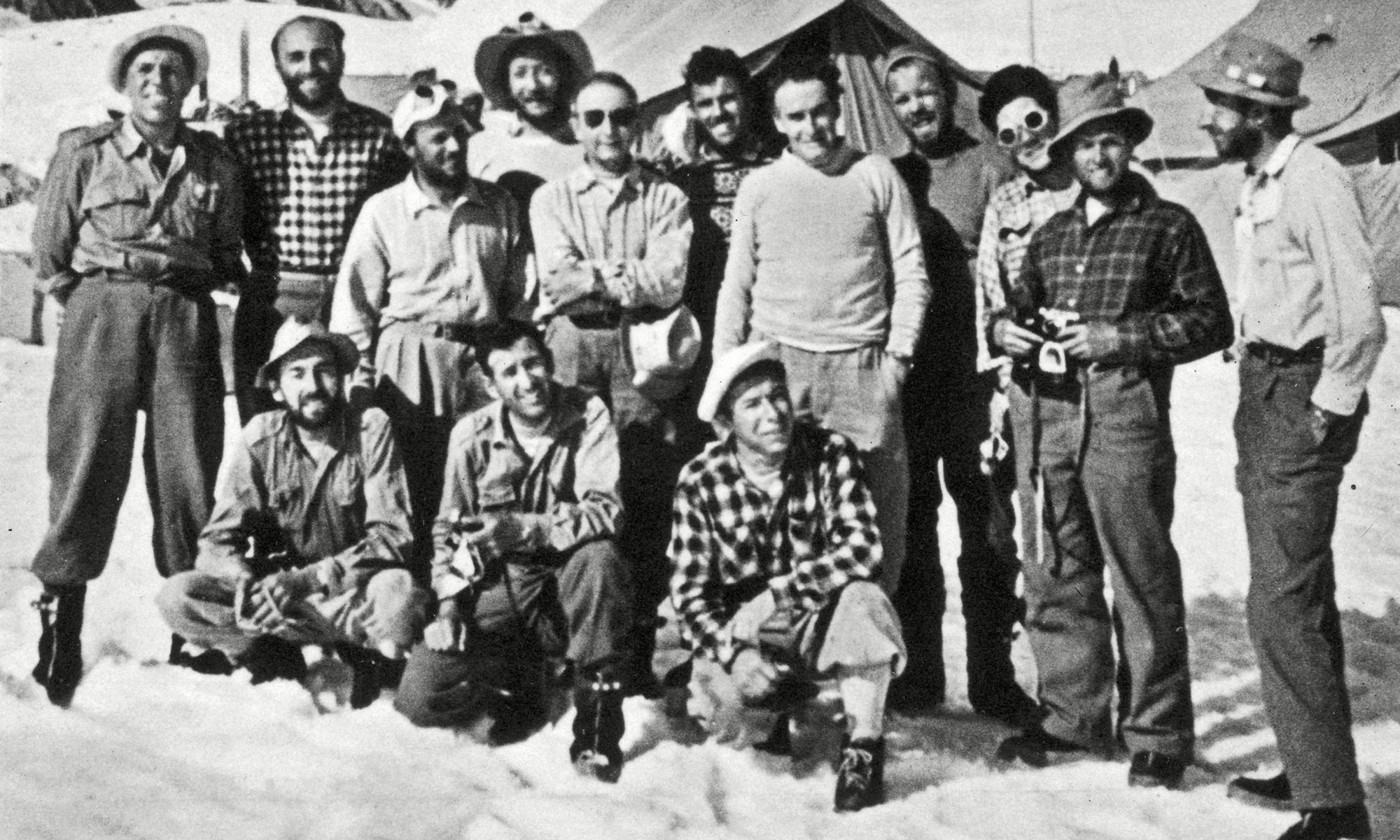

It was in 1954, one year on from Sir Edmund Hillary’s ascent of Mount Everest, that an Italian expedition led by Ardito Desio set out to climb K2. The team reached Base Camp on 28 May. There were 11 Italian climbers, amongst them Compagnoni, Lacedelli and Bonatti, the youngest climber, as well as 10 Hunza high-altitude porters, the equivalent of the Sherpas in Nepal, including Mehdi.

Desio was a divisive leader. Reports suggest he chose not to bring Riccardo Cassin, a leading Italian Alpinist, because it would have shifted the spotlight off himself. Behind his back the climbers called him "il Ducetto" - little Mussolini.

Desio would issue written orders and motivational messages for climbers. One read: "Remember if you succeed in scaling the peak - as I am confident you will - the entire world will hail you as champions of your race and your fame will endure throughout your lives and long after you're dead. Thus even if you never achieve anything else of note, you will be able to say that you have not lived in vain." Lacedelli is quoted as saying: "we just ignored him and got on with it".

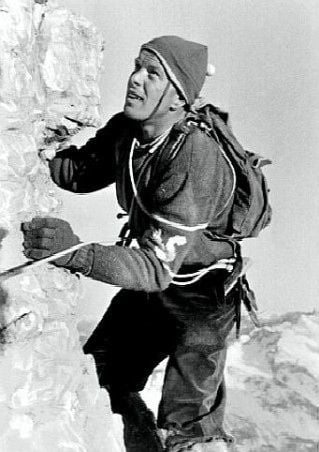

By 28 July, Bonatti, Lacedelli and Compagnoni had established Camp VIII, at the altitude of 7627m. Compagnoni and Lacedelli attempted to climb higher and establish the final camp before the summit, the now infamous Camp IX, but couldn't find a suitable location, and so they returned to Camp VIII. They also realised that they would need supplemental oxygen for the summit push.

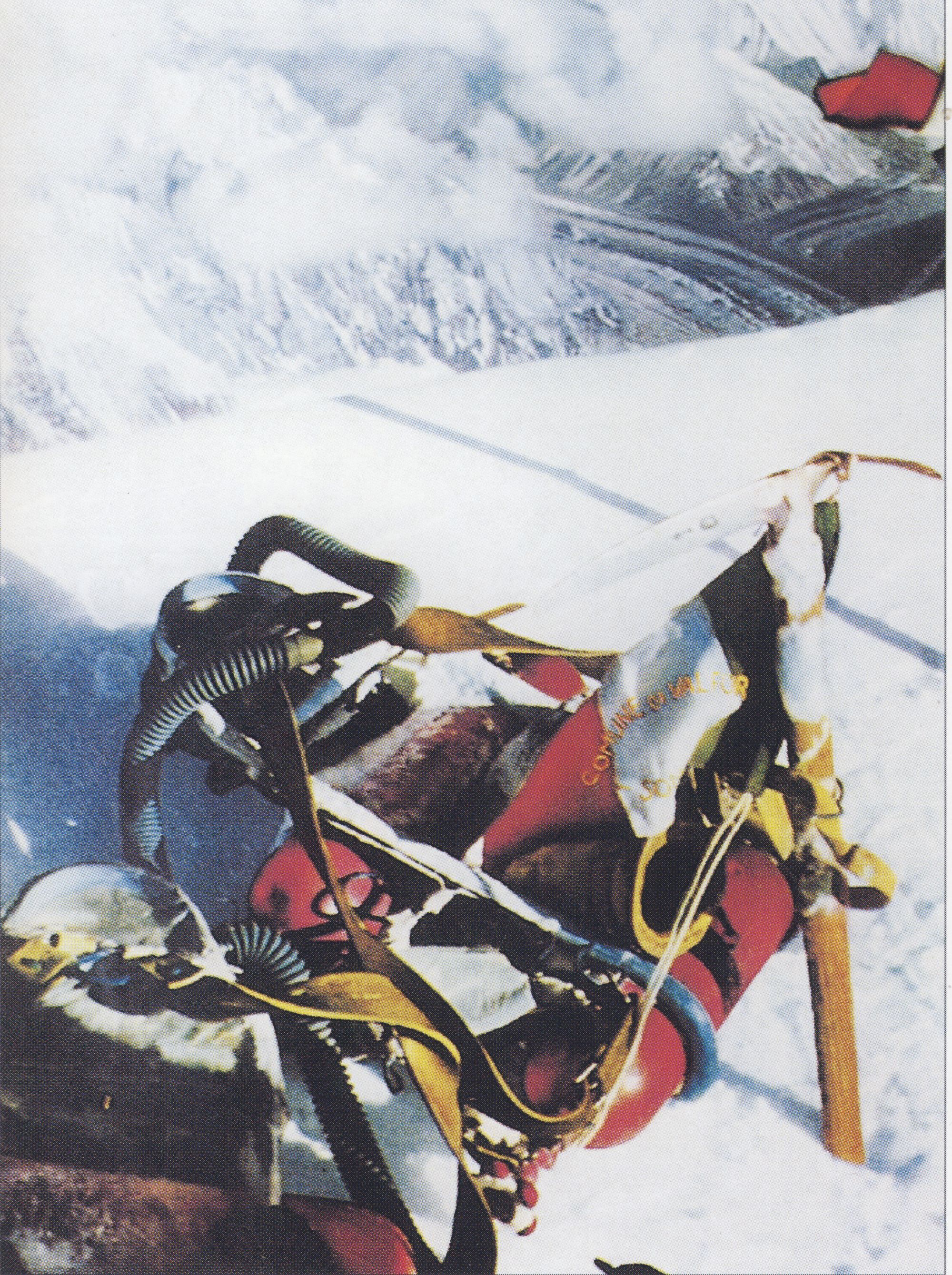

It was agreed the next day that Compagnoni and Lacedelli would go ahead and establish Camp IX, while Bonatti would descend to just above Camp VII to get the supplementary oxygen tanks, and then climb back up the mountain to Camp IX - the more challenging of the two tasks, given it meant descending 180m, then re-ascending 490m back up the mountain carrying oxygen sets weighing 18kg each.

Lacedelli and Compagnoni were to establish their final camp at around 7900m or 8000m, so that Bonatti would have less of a distance to climb with the oxygen. But instead, they established the camp at 8150m - a decision which nearly proved fatal for Walter Bonatti and Amir Mehdi.

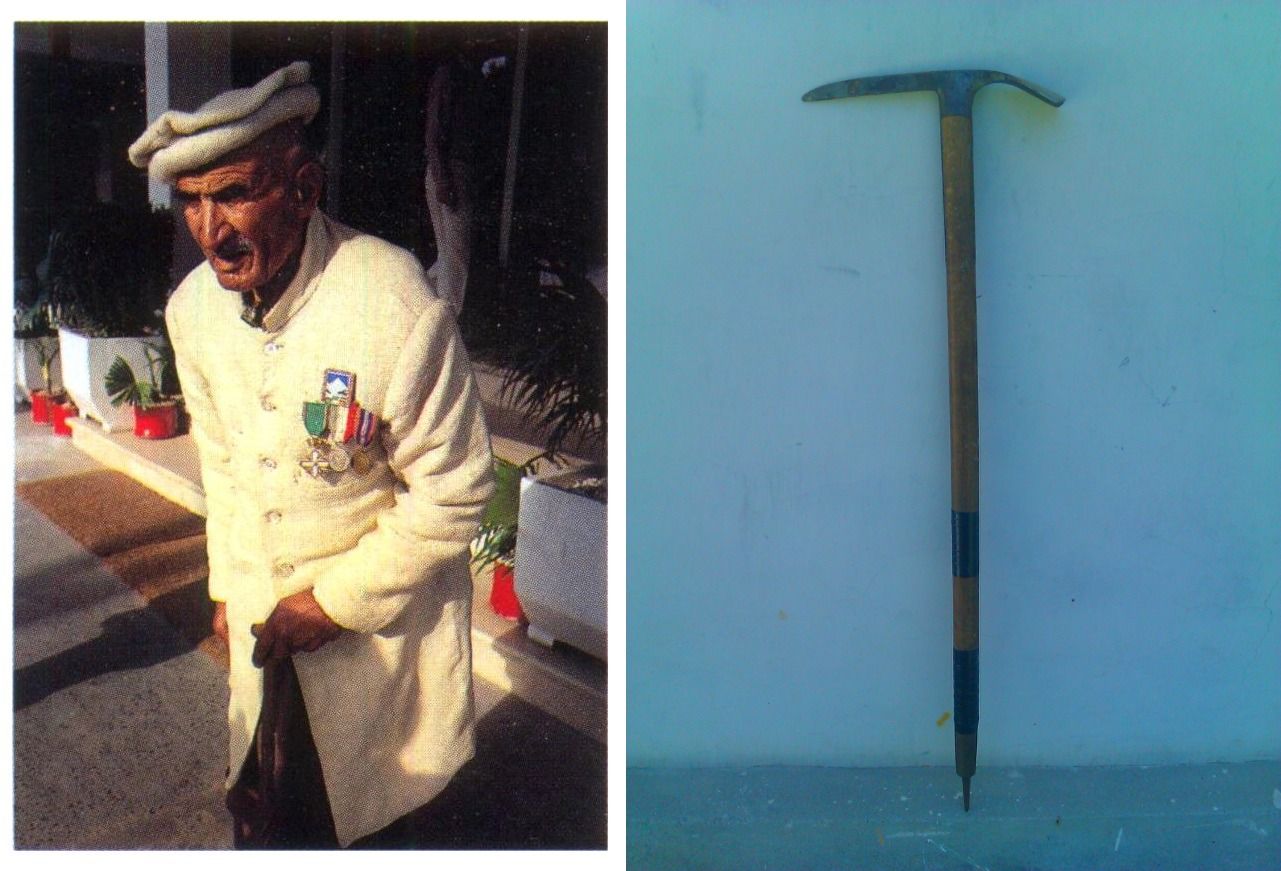

Bonatti had descended to get the oxygen tanks successfully, and convinced Amir Mehdi to help him take the tanks back up the mountain. "Other high altitude porters refused. My father agreed to the mission because he was offered a chance to get to the top," Mehdi’s son, Sultan Ali, told the BBC. But when Mehdi and Bonatti reached the spot where Camp IX should have been - at 7900m/8000m - the camp was nowhere to be seen. Bonatti shouted, and did receive a reply, but from where? He couldn’t see anyone or any camp.

My father agreed to the mission because he was offered a chance to get to the top.

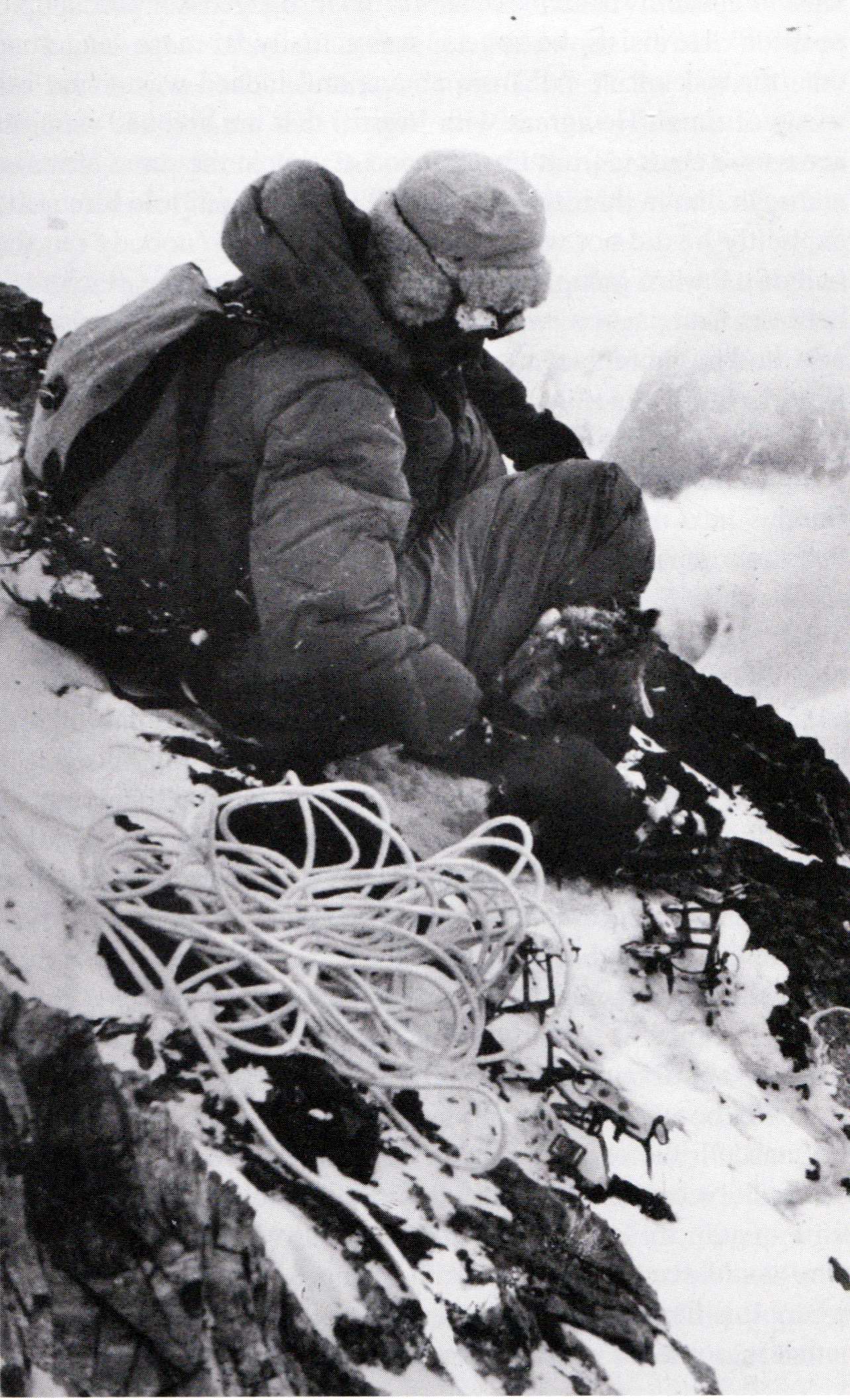

As the sun set, Mehdi and Bonatti found some tracks, but still couldn’t find the camp. Night came. They shouted and heard nothing. They had no tents, no sleeping bags and now no choice but to prepare for an overnight stay 8100m up on K2. Bonatti dug a step in the ice in preparation for the bivouac. Around 10pm a headlight appeared. It was nearby but still out of reach of Bonatti and Mehdi. It was Lacedelli, shouting to them to leave the oxygen tanks and return to Camp VIII - an impossible task. When the headlight went out, there was only silence.

Bonatti and Mehdi spent the night in the open on K2 in temperatures of -50C.

At 5.30am, against Bonatti's advice, Mehdi began to descend. Bonatti waited for the light, dug the oxygen sets out of the snow and then descended, arriving back at the camp below around the same time as Mehdi. Bonatti had frostbite on his hands, but Mehdi's feet were worse. Unlike the Italian climbers, Mehdi hadn't been given proper high-altitude boots, and reports say his boots were two sizes too small for him. Eventually, he would have all of his toes, on both feet, amputated, and would spend the next eight months in hospital. When he got home he put his ice axe away and told his family he never wanted to see it again.

It later emerged that Compagnoni had deliberately moved the location of Camp IX to prevent Bonatti joining the summit push. Compagnoni feared that the younger climber would steal the limelight from his summit attempt - especially as Bonatti was hoping to summit K2 without the use of supplementary oxygen.

It later emerged that Compagnoni had deliberately moved the location of Camp IX to prevent Bonatti joining the summit push.

With official reports and authorities keen to protect Compagnoni’s reputation in the years that followed, Bonatti was ostracised, called reckless and blamed for putting Mehdi in a position where such a dangerous bivouac was required. Compagnoni claimed he moved the camp to avoid an overhanging serac, denied all charges levied at him by Bonatti, and even accused Bonatti in an Italian newspaper of trying to sabotage his and Lacedelli’s summit push to claim the peak for himself. Bonatti sued for defamation, and in 1966 won the case.

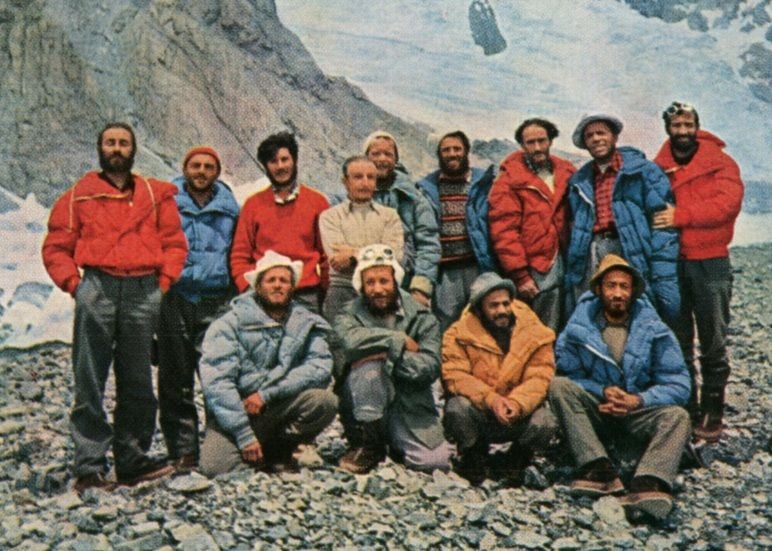

Lacedelli did not speak about K2 until the release of his book 'K2: The Price of Conquest' in 2004, in which he describes Desio as a bully, and says he opposed the positioning of Camp IX. Bonatti argued his case in several books, and in 2007, 53 years on, the Club Alpino Italiano released a revised official account of the climb which generally agreed with the then 77-year-old Walter Bonatti’s version of events.

The truths are still contested on certain parts of the K2 expedition from 1954.

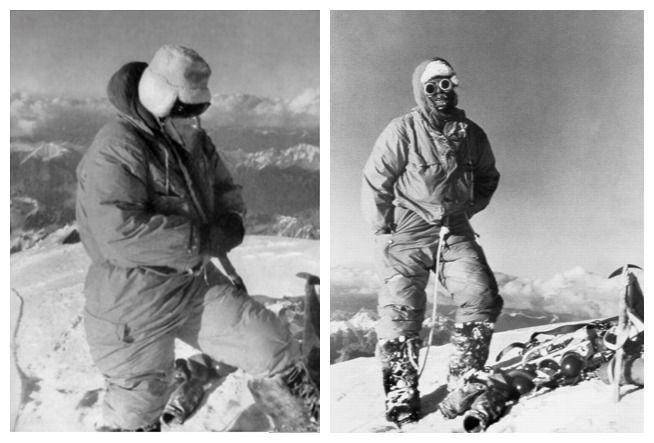

One thing is for sure. On 31 July, Compagnoni and Lacedelli woke up, left their camp on 31 July 1954 and recovered the oxygen canisters brought up to Camp IX by Bonatti and Mehdi. Soon after, the two Italian mountaineers became the first people to ever reach the summit of K2 - the world's second highest mountain.

Compagnoni wanted to spend the night on the summit, but Lacedelli wanted to head back down immediately - and got his way only after threatening Compagnoni with his ice axe. The summit of K2 was not reached again until 1977.

Inspired? Check out our full range of mountain climbing adventures. Our expert local guides know how to keep you safe in the mountains.