I know the Pentland Hills, the 20-mile hill range on the outskirts of Edinburgh, like the back of my hand. That said, I don’t actually know the back of my hand that well. I could draw you five fingers, five fingernails, a midge bite and a couple of key veins if you held a gun to my head, but after that I’d be at a bit of a loss (and curious about your violent motives).

I’m a keen mountain biker, but over the years I’ve developed my favourite routes in the hills and fallen into the habit of sticking to them. Looking at an OS Map that I dug out an unruly cupboard the other day, I’ve realised the extent to which, wonderful as they may be, my routes are that of convenience. I usually start and finish at my nearest entrance to the Pentlands, pass a few reservoirs and neglect the other 60% of the hills in the process.

This is why I love maps – physical maps. Online alternatives are great for planning, but they invite you to zoom in on your point of interest until the unknown; the rogue details that might catch your eye and get you thinking, have fallen off the face of the phone screen. Looking at and touching a physical map, you’re infinitely more likely to let your gaze wonder and discover a point of interest which will change your plans entirely, or set up a future excursion.

My OS Map of the Pentland Hills is enormous. If I was to bring it out in the hills I’d probably look like I was recording for Trigger Happy TV. But that means when I use it, I’m forced to recognise just how little of the Pentlands I see with each visit. What’s on that corner of the map, dangling tantalisingly off the edge of my dinner table… and why don’t I already know?

“There’s something wonderfully intrepid about sitting with a big, physical sheet and planning out an adventure (especially during a lockdown); imagining huge three-dimensional hills and valleys sprouting out of your map.”

There’s something wonderfully intrepid about sitting with a big, physical sheet and planning out an adventure (especially during a lockdown); imagining huge three-dimensional hills and valleys sprouting out of your map like you’re about to head off to the Amazon, even if you’re just heading a few miles up the road. My intrigue with maps has grown as I’ve delved further into their history too – and if there are two things I’ve really delved into during lockdown it’s been the history of maps and the samoyed dog hashtag on Instagram (it’s adorable).

Maps are based on facts, or at least in what is believed to be fact. These days, that tends to be accurate more often than not. But maps are also based on biases.

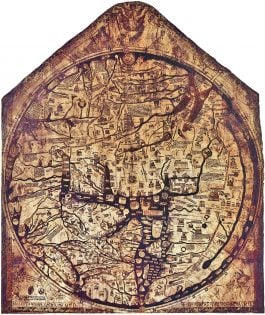

Take the Hereford Mappa Mundi, a famous medieval map of the world. Jerusalem is at its centre, and it’s set facing east, meaning it’s hard to recognise the modern world in it unless you spin it clockwise. That tells you a lot about medieval religious priorities though. Jerusalem was the centre of the world, and the reason east was at the top of the map was that it was where medieval Christians looked for the second coming of Christ.

The word for map actually comes from the latin ‘mappa’, which means “white cloth” – and it can be useful to think of map makers sitting with a blank canvas, deciding on what they deem important enough to draw, to realise the biases that maps hold.

The Mercator Projection, the map commonly taught in schools, famously shows Greenland as the same size as Africa, when in reality Africa is 14 times bigger, and did you know Google Maps redraws disputed borders on maps depending on where you’re from? From India, Kashmir appears as part of India, but on Google Maps in Pakistan, it appears as disputed.

Maps do inform, but they also project a picture of political and social culture. Scratch maps might seem playful but they’ve long irked me for how they encourage users to visit a country once and mark it as “done”, then move onto the next location, for example. I’m going to park that point there for now and take a deep dive into the scratch map and the dangers of its ideology at a later date. But even on my even on my OS Map of the Pentlands, you can see markings for hiking trails, fishing spots, car parks and mountain bike trails, all of which is common, but which paints a vivid image of how the hills are used.

The fact there are mountain bike trails I often ride which are not included on the map shows a clear prioritisation from OS towards hiking – a much more popular, common sport and the lack of any mention of paragliding, for example, accurately tells you that it’s rare to see a parachute in the hills. Enough people need to be able to make use of the information on a map for it to be included, and as such, maps end up not just documenting a setting, but also documenting the culture of that location.

“Maps end up not just documenting a setting, but also documenting the culture of that location.”

Comparing my OS Map of the Pentlands to one of a similar territory I visited in Finland a few years ago, I notice that the Finnish map has markings for recycling spots, which my OS Map does not, showing a more eco-focused culture and approach to mapping in Finland.

Maps tell stories. Whether it’s through marks of battlefields, old forts, churches and castles (the longtime inclusion of which is enough to demonstrate a class culture), or through road, trail or hill names that lead to historic nuggets. A little mark on my OS Map of the Pentlands will take you to an Iron Age fort almost impossible to find if you don’t know it’s there. Another notation will lead you to discover the hills were the scene of a Covenanters rebellion in 1666 following the Restoration of King Charles II, and lead you to the Covenanter’s Grave. There are entire historical, political and social encyclopaedias wrapped up in their intricacies.

Now that easing lockdown rules have allowed me to return the Pentlands, I’ve taken to bringing my giant OS map up the hill with me, and marking some extra, personal points of interest on it with a marker pen, as well as scribbling down the new routes that I’ve found from areas I previously have, for whatever reason, ignored. All maps are biased in their own little ways already after all, and I like the idea of my particular map of the Pentlands being a map of just that – my Pentland Hills, and how I usually use them.

Search the world map for your next adventure holiday with us now.