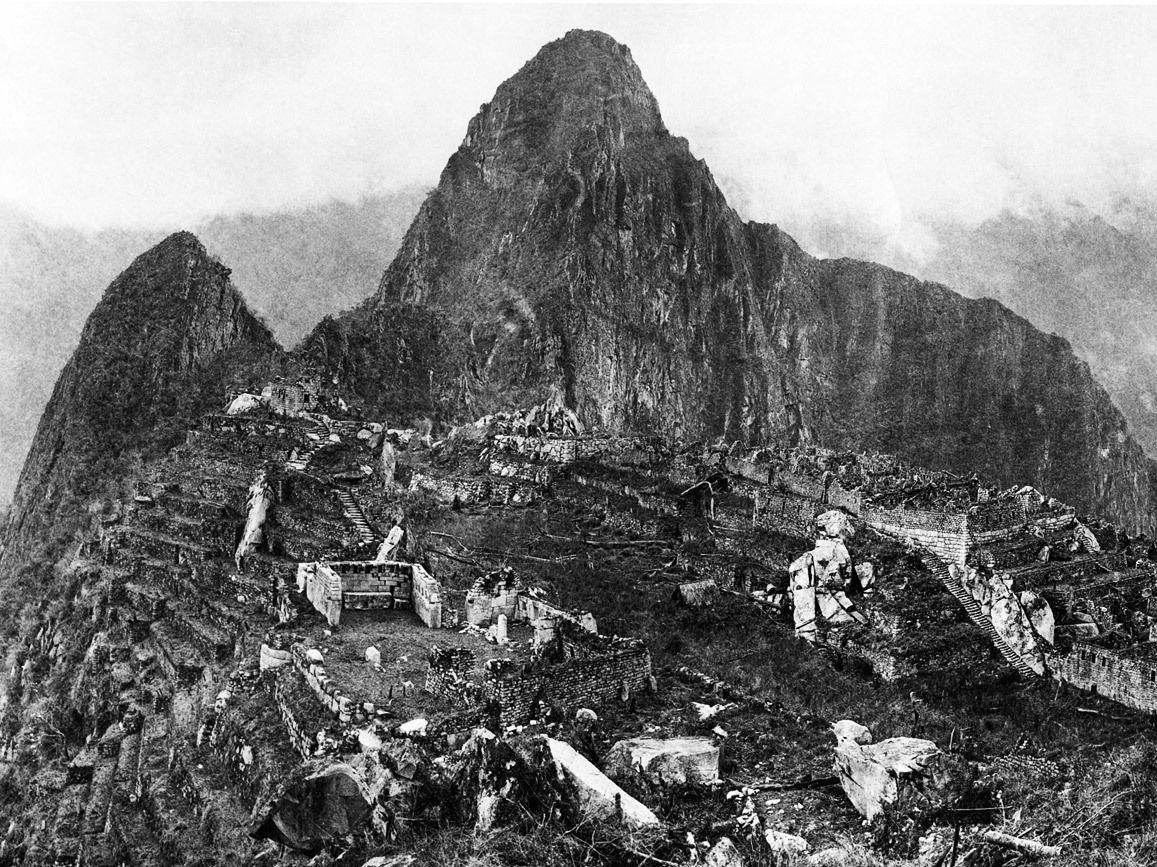

The ancient Incan city of Machu Picchu is located on the eastern slopes of the Peruvian Andes along a prominent ridge between two peaks, surrounded by mist-wreathed tropical forest. This ancient Incan city consists of approximately 200 structures, including the round-walled Temple of the Sun and the Temple of the Condor, which is built into a rock outcrop said to look like spreading wings. The site is crisscrossed with granite terraces, which cling precipitously to the slopes.

We recommend visitors arrive early, to beat the crowds. Watch as the sun rises over the mountains, bathing the ruins in golden light. Climb up to Guardian’s House and you’ll see the entire complex from above. The terraces, temples and ramps appear to emerge almost organically from the contours of this rugged landscape, an embodiment of Incan ingenuity. Small wonder that it’s one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

These days, around 1.5 million people visit Machu Picchu each year. But for many centuries it lay hidden from the wider world, covered by the forest that surrounded it. Then, in 1911, it was rediscovered by the academic and explorer Hiram Bingham - at least, that’s what some history books would have us believe.

In fact, Bingham didn’t actually find the ruins on his own. For a start, he was guided there by members of the local indigenous community. And when he arrived he saw a charcoal inscription on a temple window. “A. Lizárraga 1902.” Someone had arrived before him.

This is the story of how Machu Picchu was ‘lost’ and then rediscovered, not once but twice.

Machu Picchu was built during the reign of Inca Emperor Pachacuti, and was in use from around A.D. 1420 to A.D. 1530, according to an archaeological dating study. The Incas were master builders, who created this vast citadel of temples, plazas and palatial houses out of large stones that fitted perfectly together without the use of mortar. Transporting the building materials was an impressive feat in itself, as they would have had to carry these large stones up steep mountain slopes.

There are several theories why Machu Picchu was abandoned, including a smallpox epidemic or the death of the emperor (which meant the seat of power was moved to a different location). Some historians believe that it was simply the remote nature of the site that caused it to be deserted. Others think it was to do with the Spanish invasion of Peru - that the Incans left the city to go to war, and wanted to keep it safe from the colonisers.

If that was the case, they were successful. The Spanish never discovered Machu Picchu. And as the Incans died or dispersed, the city in the mountains faded from their collective consciousness.

Who Found Machu Picchu?

Hiram Bingham poses outside his tent on Machu Picchu during his 1912 expedition (left) and Agustín Lizárraga Ruiz (right). Photos: Wikimedia Commons

For hundreds of years Machu Picchu remained forgotten in the jungle.until Agustín Lizárraga Ruiz quite literally stumbled across it in 1902.Lizárraga was a Peruvian farm worker who lived in the region, and worked on a farm called Collpani Hacienda. In 1902 he organised an expedition down into the Urubamba Valley, with the goal of finding new areas for cultivating crops and sourcing wood. He was accompanied by his cousin Enrique Palma Ruiz, the manager of Collpani Hacienda, and another worker, Toribio Recharte.

Together, they picked their way through the dense foliage. As they climbed up the steep slopes of Machu Picchu, Lizárraga discovered the stone walls of ancient buildings, overgrown by the jungle. Thoughts of farmland were forgotten in the excitement of historical discovery. Lizárraga spent the day exploring the citadel, uncovering more and more buildings. It was when he discovered the Temple of the Three Windows that he felt moved to write his own name for posterity.

Lizárraga told friends and family what he had discovered. But he didn’t inform the authorities, or the press. A year later, in 1903, he sent Toribio Recharte and his family back to Machu Picchu. They cleared some of the terraces built by the Incans and began to grow corn, beans, squash and more; another family was sent to join them a few years later. Lizárraga even organised a small tourism trip to Machu Picchu, so his acquaintances could see the ruins.

However, it's not always Lizárraga who is credited with the rediscovery of Machu Picchu - it's often a man called Hiram Bingham. He was a professor of Latin American history at Yale, and a keen explorer. Bingham learned mountaineering skills from his father, a missionary in the Pacific. In fact, he’s said to have been one of the inspirations for the character of Indiana Jones.

In 1911, Bingham directed an archaeological expedition to find Vitcos, the last capital of the Incas. He visited Urubamba Valley to ask locals if there were any ruins in the area, and was directed towards Machu Picchu. His field journal describes the discovery of huilca plants, a type of “narcotic snuff”, before pushing on past “the house of Señor Lizarraga, first of modern Peruvians to write his name on the granite walls of Machu Picchu.”

Bingham and his men continued further into Urubamba Valley, until they reached the village of Lucma and the house of the governor, Mogrovejo.

We offered to pay Mogrovejo a gratificación of a sol, or Peruvian silver dollar, for every ruin to which he would take us

“We offered to pay Mogrovejo a gratificación of a sol, or Peruvian silver dollar, for every ruin to which he would take us, and double that amount if the locality should prove to contain particularly interesting ruins,” he writes. “This aroused all his business instincts. He summoned his alcaldes and other well-informed Indians to appear and be interviewed. They told us there were “many ruins” hereabouts!”

Eventually, Bingham and his team were guided towards Machu Picchu, where they met the two farming families that Lizárraga had sent to cultivate the city’s terraces. After giving the team refreshments, they were shown the ruins.

“Hardly had we rounded the promontory when the character of the stonework began to improve,” Bingham writes in his journal. “A flight of beautifully constructed terraces, each two hundred yards long and ten feet high, had then recently been rescued from the jungle by the Indians. A forest of large trees had been chopped down and burned over to make a clearing for agricultural purposes.

“Crossing these terraces, I entered the untouched forest beyond, and suddenly found myself in a maze of beautiful granite houses! They were covered with trees and moss and the growth of centuries, but in the dense shadow, hiding in bamboo thickets and tangled vines, could be seen, here and there, walls of white granite ashlars most carefully cut and exquisitely fitted together.”

I entered the untouched forest beyond, and suddenly found myself in a maze of beautiful granite houses!

Bingham returned to America and told his contacts what he had discovered. He returned to Machu Picchu a year later, leading an archeological expedition sponsored by Yale and the National Geographic Society. This led to the transfer of over 5,400 artefacts - including human remains - to Yale for research (something which angered Peruvians, especially since it was a century before they were finally returned).

The entire April 1913 edition of the National Geographic magazine was devoted to his ‘discovery’ of the ruins - and Lizárraga’s name was never mentioned. The photographs that Bingham published in the article don’t show the many terraces already cleared of vegetation and planted.

In Framing a Lost City. Science, Photography, and the Making of Machu Picchu, author Amy Cox Hall describes this as a process of erasure.

“Although Bingham referred to Lizárraga as the discoverer in his first articles and speeches, and even in Inca Land (1922), the presence of Lizárraga’s signature faded until, in his final version of the story, Lost City of the Incas (1952), Bingham claimed to have found the site himself.”

Lizárraga was not alive to defend his discovery, having drowned in Urubamba River in 1912. So for many years, it was Bingham’s story that the world - specifically, the western press - told about the story of Machu Picchu.

But Peruvian academics, scholars and journalists railed against this narrative, which they saw as positioning Machu Picchu as a space that existed for foreign tourists. When Peruvian Prime Minister Alan García Perez announced the centenary of the Machu discovery Picchu in 2011, there were some vocal dissidents. A special supplement was published in La Primera, a prominent Peruvian newspaper, about the necessity of acknowledging the significant contribution of Agustin Lizárraga Ruiz in rediscovering Machu Picchu.

On 4th July 2011, during the centenary celebrations, Américo Rivas Tapia published a book entitled Agustín Lizárraga: El gran descubridor de Machupicchu. Thanks to these efforts from writers and historians, Lizárraga’s role is now more widely acknowledged. But it’s also important to acknowledge the contribution of the indigenous guides and farmers who led Bingham to Machu Picchu, and who were aware of its existence long before it became known to the western world.

How to Get to Machu Picchu

Reach Machu Picchu by first traveling to Cusco, Peru. From Cusco, take a train to Aguas Calientes, the nearest town (two to three hours). From Aguas Calientes, take a 30-minute bus ride or hike up to the ruins. Advance tickets and permits are required for entry.

More intrepid adventurers prefer to trek to Machu Picchu. It can be reached via the Inca Trail, a 26 mile (43km) route, or the quieter and more scenic Salkantay route (46 miles/ 74km). The latter takes you through the scenic Humantay Mountains, over the Salkantay Pass (4,630m/15,190ft) and past Llactapata, another significant Incan ruin.

Read more:

- A Guide to the Sacred Valley of the Incas in Peru

- Salkantay Trek to Machu Picchu: The Epic 74km Alternative to the Inca Trail

Inspired? Join us on an adventure to Machu Picchu.