On 17 September 1811, Dr Friedrich Parrot stood on the summit ridge of Mount Kazbek, the mighty 5,034m mountain in the Caucasus, on the present-day Russian-Georgian border.

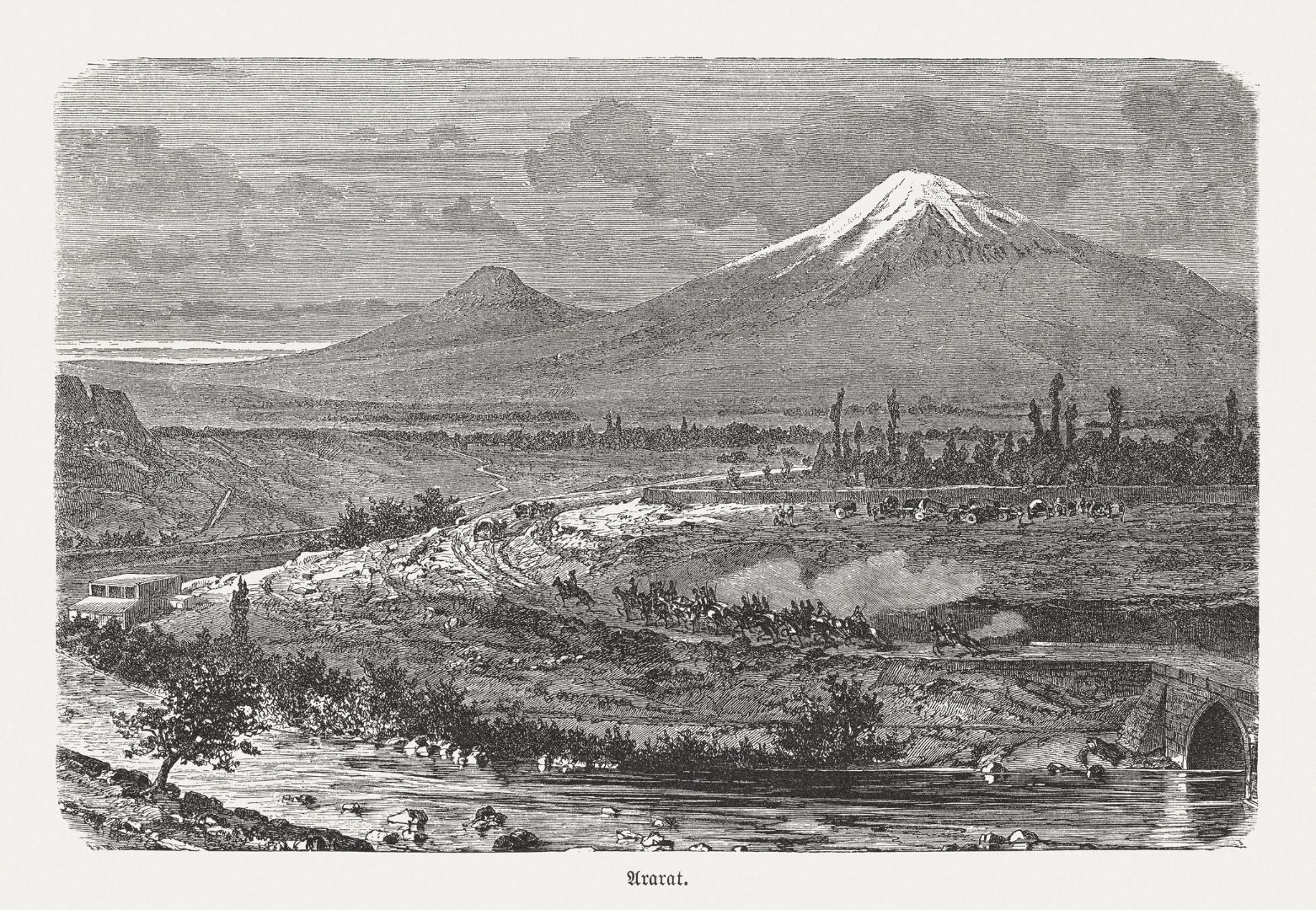

The peak of Kazbek, unseen by human eyes at the time, lay only 500 metres beyond, but when a blizzard blew in, Parrot was forced to abandon the summit push. Before he left, a momentary break in the clouds allowed Dr. Parrot to look out to the silver crown of Mount Ararat in the distance - the snow-capped volcano in the extreme east of Turkey where, legend has it, Noah’s Ark came to rest after the great flood. Parrot left Kazbek with a new mountain in his heart. One day, he thought, he would become the first man to reach the summit of Ararat. He was right.

Friedrich Parrot was born on 14 October 1791 in Karlsruhe, Germany. He studied medicine and natural science at the University of Dorpat (now the University of Tartu, in Estonia), where his father Georg was the first rector, and his interest in science led him to a life of mountaineering. This was a time when climbing simply for enjoyment was still socially stigmatised. In an essay on Ararat and Parrot, Edward Peck writes that it was not “seemly or justifiable to climb mountains for their own sake unless there was a scientific objective in view.” Parrot carried a barometer on most climbs, and established accurate heights of many mountains as a result.

Still, the German scholar spoke about the mountains in much the same spiritual way a modern mountaineer might. “There is no study more delightful or practically more useful than that which makes us acquainted with the heart and its inhabitants,” opens the preface to Journey to Ararat, the 1834 text written by Parrot, translated into English by William Desborough in 1846.

One soldier “had brought no warm clothing and had to be wrapped overnight in the thick grey blotting paper intended for preserving botanical specimens...”

Parrot had climbed in the Alps, Pyrenees and the Caucasus before attempting Ararat. The issue with Ararat was that it was between the Ottoman and Persian Empires, rendering it “as insecure for Christian travellers as during open war.” That changed after the Russo-Persian War (1826-28); which ended with the Treaty of Turkmenchay and put Ararat firmly in Russian terrain.

Parrot’s father Georg had a personal relationship with Tsar Alexander the First, the Emperor of Russia from 1801-1815, and while Alexander died in 1825, the family connections carried to his successor Nicholas I. Parrot was able to use these connections for sponsorship purposes and to gather a team - namely, a military courier named M. Schütz (sent on order of the Tsar himself), mineralogist M. von Behaghel, astronomer M. Vassili Federov and two medical students, M. Julius Hehn and M. Carl Schieman. The group left Dorpat on 11 April 1829 and began the 2,330-mile journey to Ararat, travelling across western Russia, passing “the imposing magnate of the Caucasus Alps in full splendour,” and riding above Kasbegi and past Kazbek.

Ararat had long been considered an unclimbable mountain. When French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort visited the area in the early 1700s, he reported that the summit as “inaccessible”, both by “reason of its great height, and of the snow which perpetually covers it.”

When Parrot rounded the shoulder of Alagöz and saw Mt Ararat for the first time, his confidence in the climb grew. “I was surprised to find its northwestern declivity much less abrupt than it had been represented in the sketches,” he wrote. “I was so confident that the assumed inaccessibility of its summit must be unfounded, that I could not conceal from my companions the hopes I began to entertain of reaching the summit myself.”

The party were delayed for two months while they waited for “an attack of plague” to cool in Armenia, then reached the 150 miles to the Armenian monastery of Echmiadzin on 1 September. Here, the 24-year-old Khachatur Abovian joined the group as a local guide and translator. A deacon and writer, he would go on to become the “father of Armenian literature”.

Here, they were also shown a revered piece of wood, said to be a fragment of Noah’s Ark. Peck writes that local superstition said it “had been acquired by a monk who, over 1,000 years previously, had set out to climb Ararat but had grown tired and fallen asleep. An angel had appeared to him in a vision, and had pressed the piece of wood into his hand, telling him that his devoutness had released him (and others) from any further need to climb the mountain. Local belief in this myth was strong and since that day, Ararat had been held too sacred to climb.” This belief would bring many to criticise and cast doubt on Parrot’s summit efforts.

The group set up base camp beneath Ararat, at the Armenian village of Arguri, close to the Monastery of St. James, where Noah himself was alleged to have planted a vineyard. Peck writes that they slept at the “foot of the Ahora Chasm, the cleft in the north-east slope of Ararat where a volcanic explosion a few years later, in 1840, destroyed the monastery and the village.”

The group’s first two attempts on Ararat were unsuccessful. On the first, they found the cold too much. One soldier “had brought no warm clothing and had to be wrapped overnight in the thick grey blotting paper intended for preserving botanical specimens,” writes Peck. Parrot saved Schieman from a slip, with the use of his staff and “excellent many-pointed ice-shoes”.

Their second attempt was via a more gentle route on the northwest side, suggested by Arguri village chief Stepan Khojiants. They carried a huge cross with them, to erect on the summit, but after a night on the snowline planted it at 4885m. They were forced to turn back by worsening weather, a lack of time, and “inadequate means for spending a night on the icy pinnacle.”

Parrot wrote that his “only consolation was the hope of another and more successful attempt.”

It would indeed be third time lucky for Parrot and his party. On 7 October they camped at 3,962m and enjoyed a “hearty meal” - though the Armenian party-members, including Abovian, were fasting. Several party members turned back because of the glacial conditions near the summit, but the others, Parrot writes, "pushed on unremittingly to our object, rather excited than discouraged by the difficulties in our way.” The group passed the height of the previous cross, and endured several false summits. They remained buoyant, Parrot writing: “on calculating what was already done and what remained to be done - on considering the proximity of the succeeding row of heights, and casting a glance at my hearty followers, care fled, and “boldly onward!” resounded in my bosom.”

Eventually, they had the summit in sight.

“I pressed forward round a projecting mound of snow, and behold! Before my eyes, now intoxicated with joy, lay the extreme cone, the highest pinnacle of Ararat,” Parrot writes. “A last effort was required of us to ascend a tract of ice by means of steps, and that accomplished, about a quarter past three on the 9th of October, 1829, we stood on the top of Ararat.”

Abovian wrote: “Our souls were enveloped with happiness and were overcome by unimaginable gaiety; we began to run about in this and that direction to view the lower-lying valleys and ridges.” Parrot noted a nearby saddle, which “may be supposed to be the very spot on which Noah’s ark rested, if the summit itself be assumed as the scene of that event, for there is no want of the requisite space,” and Abovian erected a small cross over the north-east edge.

They toasted Noah, then descended. “The evening of our return was celebrated by the discharge of some rockets,” writes Parrot, “which we owed to the kindness of M. von Dunant, captain of artillery in Erivan [modern day Yerivan].”

On his way back home, looking back out over Kazbek, Parrot noted “the well-known rocky summits and plains of ice and snow which I had so often gone over' eighteen years earlier”, and he finally returned back to Dorpat in March 1830, almost a full year after he had departed.

Impressed by Abovian’s thirst for knowledge, Parrot arranged for a Russian state scholarship to be given to the deacon at the University of Dorpat. Abovian studied in the Philosophy faculty from 1830-1836, and then returned to Armenia. He went on to climb Mt Ararat twice more, in 1845 with a German mineralogist, and in 1846, with the Englishman Henry Danby Seymour.

Inspired? Check out our mountain climbing tours, hiking in Armenia trip, or go where Parrot couldn't and climb Mount Kazbek.

This article contains affiliate links. Which basically means we make a little commission if you click through and buy something. It doesn’t cost you anything, and it just means we can do more good things in good places.