We do not often talk about the abundance of human excrement in our wild places. Instead, the topic of human faeces tends to go unmentioned, allowing the issues to build up like overflow diarrhoea, blocking the bowels before exploding out in a couple of sensationalist news articles each year. Then, we're confronted by the fact that the Snowdonia mountain path is apparently covered in human faeces, or that waste on Everest is becoming a health hazard to climbers, seemingly out of the blue.

In truth, nothing is less sensational than a human taking a poo, but dealing with our outdoor waste in a hygienic and environmental manner is a skill even many of the biggest proponents of ‘leave no trace’ have never learned or rarely discuss - simply because it is deemed too embarrassing or vulgar to talk about.

Education is a never ending struggle. But it is by far the most essential ingredient. Increased enlightenment means less regulation.

“There’s a degree of coyness about the whole thing, because it’s not mentioned in polite society,” says Davie Black, Access and Conservation Officer of Mountaineering Scotland. “But we have to grasp that nettle, because it is an issue. You can do it effectively and safely, but you need to plan ahead. It’s a public health issue, because bacteria can get into soil and spread - and in certain places it can take a lot longer to rot down than many people think it does.”

Besides the obvious issues around the beauty and smell of our wild places, the impact of waste on areas with heavy footfall - namely national parks - can be environmentally damaging, and germs and bacteria can infect water sources.

How to Take a Poo Outdoors

Mountaineering Scotland has an excellent Minimal Impact Advice guide on their website, which includes a section on outdoor toileting.

“Urinating is fairly straightforward,” it reads. “Don’t pee near open water or burns and stay well away from your campsite, buildings or any other shelter.” They specify walking a minimum of 30m away from such spots, notably not upstream or downstream, but away from the site.

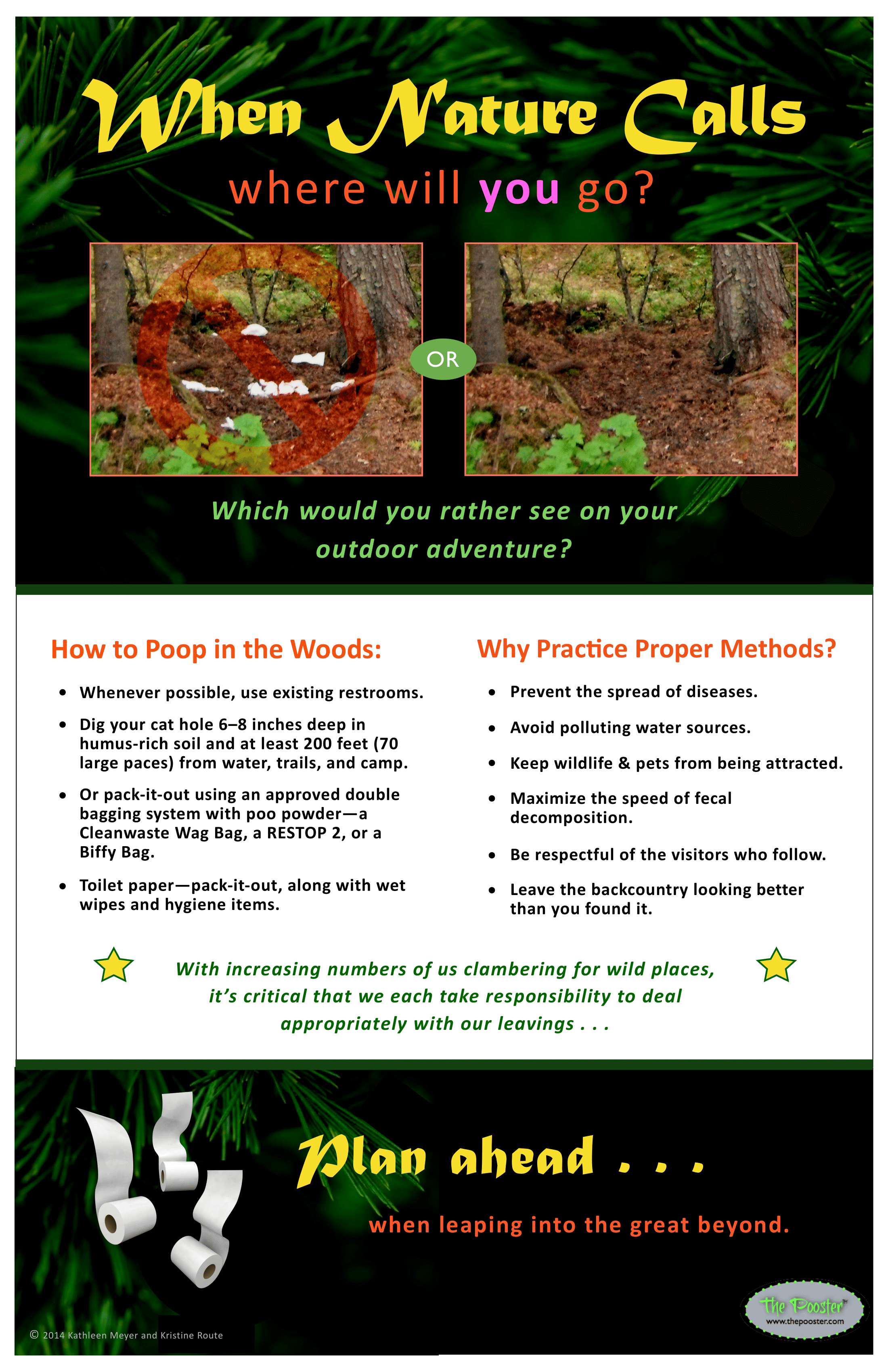

When it comes to solids, there are two options: “dig a hole and bury it, or bag it and carry it out.”

For the burial method: bring a small trowel, toilet paper, and some small waste disposal bags. Choose a spot 30m away from paths, open water or shelters, dig a small pit, six inches deep, poo in the hole, drop the toilet paper in, or bag it to bin later. Never bury wet wipes or sanitary items. Fill in the hole with the excavated soil, and then wash your hand with water or with sanitiser.

It’s a sensitive issue but it would be great for there to be an ethos of packing out in fragile environments, or places where it won’t rot down quickly.

“We try to advocate to people not to crap round the back of a nice boulder, because other people might want to shelter from weather there,” Black says. “It’s about having awareness and trying to establish that ethos.”

To bag the poo and carry it out - the more visceral, but better of the two options - pack a biodegradable dog poo bag or food waste bag and a sealable container. Poo in the bag, tip it up and put it in the container, or double bag it. Do not discard plastic bags of poo into toilets that require pumping out, as this can bugger the pump. Instead, carry it out and bin the waste (or if in the US, look into poo powder bags), and later disinfect the plastic container for reuse.

While not commonly done in the UK, carrying out is truly how to leave no trace.

“We always advocate go before you go, but if you’re travelling a distance, you may need to go again,” says Davie. “We don’t have a culture of packing out in Scotland, and I think many would find it stressful to carry their poo back out with them, in a container and in a rucksack. It’s a sensitive issue but it would be great for there to be an ethos of packing out in fragile environments."

Black explains: “A lot of people think that since it's organic waste, [faeces] will rot down quickly, which may be fine in the lowland areas, but as you get further north in latitude and further up in altitude, you'll find that it doesn't break down quite as quickly - so there is a lingering issue, which is a problem.” When the snow melts, the faeces of snowsports tourers often emerge on hillsides, for example, and the UK's highest mountains suffer more due to altitude and footfall.

In Scotland, where hikers have the right to responsible access, and so more areas to choose from, the issue is less prominent than in the rest of the UK.

“It’s more dispersed in Scotland,” says Black. “In England, you're corralled into national parks and it's all in the one area, whereas we've got a third of the landmass of Britain to go wandering in. There's that solution to pollution of dilution, but there is a capacity issue with certain areas.”

Loch Lomond is one such area. “It's more problematic near where people are parking and camping,” he says. “It's not so much elsewhere, but it doesn't mean that it doesn't happen. It’s just easier to hide your presence when you’re away from the hotspots - so you find that the national parks and places like Ben Nevis, where people congregate, tend to suffer the most.”

Lack of land access in English and Wales means a large number of hikers are directed to comparatively small areas - meaning the footfall to certain mountains is unusually high.

Digging into the Dirt

In April, a guide on Snowdon told the BBC that over Easter the trails were “covered in human stools” - and not the carpentry type. One man was even caught “defecating on the mountain's railway line,” the article stated.

This is not to say the issue is worse on Snowdon than other popular mountains, but it does have a high footfall, leading to issues - and although quickly forgotten, the issue finds its way into the mainstream media every couple of years.

“It’s not a new thing,” says guide Jim Young, founder of Adventurous Ewe and a man who “can’t even begin to imagine” how many times he has summited Snowdon. “But it is a bad situation.”

“The facilities aren’t great. At Llanberis, a lot of the toilets don’t open till 10am, which means there are often no facilities for people before they start. The cafe is closed at the moment, mainly due to the railway line needing repairs, so there’s no toilets at the top either right now. If you put a railway line and a cafe on a mountain and you have nearly half a million people going up it each year, and you’ve got no toilet facilities, then you’re going to have this problem.”

Young does say, though, that the issue is perhaps dramatised by the media.

“I’ve never come across anything like that [BBC report] on Snowdon,” Jim says. “I wouldn’t drink the water on Snowdon, and there’s no way I would tell any of our groups to drink out the streams. If you go behind a rock or a wall near the path, at a certain point, then you could see [faeces], but that’s also the case on Kilimanjaro and on Toubkal, where people camp near the refuge.

“I’ve never seen the paths on Snowdon as bad as described in the BBC report, and I’ve certainly never seen anyone going in the middle of a path.”

Young points out, with a laugh, that it’s worth remembering that pooing behind a rock is never a hiker's plan A, either: “This is not something people choose to do or want to do. We have people on treks sometimes that won’t eat or drink because they don’t want to go to the toilet. Nobody wants to go and sit behind a rock and do that! It’s just managing it and providing the proper facilities.”

This is not something people choose to do or want to do. We have people on treks sometimes that won’t eat or drink because they don’t want to go to the toilet.

For Young, education and preparation are key - for this issue and others.

“Our guides actually take bin bags with them and pick up litter as they go,” says Jim. “Then we try and manage [the toilet situation]. There’s a briefing at the beginning of the climb, pointing out where toilets are and making everyone aware there are no toilets when they get going. I think many people are maybe not aware that the cafe isn’t open and go unprepared up the mountain.

“But some people are always going to get caught short when you’ve got 500,000 a year going up a mountain. So I think being aware and carrying bags that can take waste or toilet paper back out with them - that’s all you can do really, isn’t it?

“It’s quite controversial. Some people think they should put a toilet on the Llanberis path halfway up the mountain. How they would do that I don’t know. Others think it's a mountain environment and you shouldn't have any structures on there, to keep it natural, and it is in a National Park - but then also you have got those masses, so I don’t know what the long term solution is.”

How to Shit in the Woods

Kathleen Meyer is an author and environmental activist who lives at the base of the Bitterroot Mountains in Montana. Her bestselling guide ‘How to Shit in the Woods’, first published in 1989, has sold more than three million copies in eight languages, and is now on its fourth edition.

“It became my mission to drag this taboo topic into the sunshine,” she says.

Like Young, Meyer recounts “experiences with more than one [adventurer] who resorted to holding it for a six-day river trip. I couldn’t believe that was digestively possible.”

Her guide was “driven by the sights of toilet-trashed river banks and woodland trails” and aims to impart “essential environmental precautions about wild country toilet habits and offer assistance to the latest generation of backwoods enthusiasts still fumbling with their drawers - as I had."

The idea for Meyer’s book originally came from her time spent as a whitewater rafting guide in the 1970s, when the sport was just taking off.

“When we hit a night’s camp, in those days, women were instructed to go, say, upstream, and men downstream,” she says. “A paper bag, shovel, and roll of toilet tissue were stationed at the edge of camp. As the guides became more comfortable and casual about engaging in the subject, things went better. Basically: dig a hole six-eight inches deep in rich, humus soil, with good enzymes that promote rapid decomposition, squat over it, cover your deposit well, and drop your used paper in the paper bag, which will be burned in the morning’s campfire.

Numbers matter. Soon we were digging up someone else’s deposit to make one of our own.

“But drawbacks were obvious. People puttered thirty paces around the first bend, stepped two feet off the trail, and dropped their britches. The next person out for a stroll stumbled right into them. Women, though trying their best, contorted into the most excruciating positions. And no one wanted to be seen bringing a bundle of tissue back to the bag. Most apparent was that big-rapid rivers flow through deep, narrow canyons with limited beaches for camping. Those lovely spots were expected to accommodate a new party of 10-30 every day.

“Numbers matter. Soon we were digging up someone else’s deposit to make one of our own.” Responsible access is key when accessing wild places.

“Back when we were only small bands of hunter-gatherers roaming with the seasons, Mother Earth could easily absorb our waste,” says Kathleen. “Recent decades have seen visitation in parks and wildlands balloon well beyond sane limits of vehicle and foot traffic, and bathroom facilities. And then Covid hit, luring hordes of newbies to the outdoors, in search of fresh air.”

Answering Nature’s Call: The Solutions

Talking to the experts, the two recurring topics that seem to present a potential solution are education and infrastructure.

“The problem in the recent past has been that a lot of public toilets have been closed due to a lack of funding for maintenance,” says Davie Black. “Especially with Covid. Funding is reasonably straightforward [for building toilets], but you need a revenue stream to maintain them in the future. That’s why organisations and people are loathe to go down that road. They get locked into it and one day they may not have the funds to continue with it.

“Then do you charge for it or not? Will people pay the money? If you're charging for car parking, do you charge for the toilet on top of that, or will that disincentivise people? Is it a flush toilet, which then needs to be connected to the mains, or a composting toilet, in which case, do most people know how to use it? People tend to think other people will just deal with these issues.”

Kathleen Meyer adds that such funding, and change, often only comes on the back of demand - so continuing the conversation is important.

As a planet, we produce people faster and in much larger numbers than books and instructors.

“Political will,” Meyer notes, “often starts with people complaining.”

Meyer also recommends various degrees of regulation, from pack-it-out systems, which could be inspected “to make sure they are adequate for the number in your party and length of your trip” to park reservation requirements and improved services. Some parks, she notes, “will sometimes supply hikers with biodegradable double-bagging kits, which contain “poo powder” (similar to what’s used in space shuttles) that cuts down on smell and starts the faecal biodegrading.”

The real emphasis must be on education, though.

“Education is a never ending struggle," Meyer says. "But it is by far the most essential ingredient. Increased enlightenment means less regulation. It’s outfitters, guides, rangers, and outdoor schools who are at the forefront of instilling awareness. Signage is important: ‘Leave No Trace’ or ‘Poosters’ (poo instructional posters) and staffed information tables at trailheads.”

In the perfect world, this would take place before hikers reach the trailhead.

“It would certainly be helpful if the subject of pooping outdoors were taught in grade school,” she says. “As a planet, we produce people faster and in much larger numbers than books and instructors. Those first heading into the backcountry don’t stop to think they have grown up on porcelain flushing toilets. People tend not to think ahead, often out of embarrassment to ask.”

She continues: “Regular backcountry sojourners, those who develop a deep love of Nature’s grandeur, quickly become experts in toilet etiquette and are often the ones to clean up befouled favourite sites and set about instructing others. Newcomers easily get hooked on the beauty and adventure of wild country, but largely remain unschooled.”

So? Plan ahead. Carry out your faeces or bury it with thought. And most importantly, don't be afraid to talk to your loved ones about pooing outdoors.

Inspired? Check out our range of adventure holidays in the UK now!