As the airplane begins its final descent into Bhutan’s only international airport, a house flies past my window. I do a double take. It’s been a long, sleepless flight from London, via Bangkok. We’re flying through layers of low-hanging cloud. Perhaps I’m imagining things? Yet as we emerge into a patch of clear sky, another house floats past. And then a whole village.

Eventually, we pop out beneath the clouds, my brain fog lifts, and it becomes obvious that the buildings drifting past are not, in fact, airborne—they’ve just been built high up the sides of the mountains we’re flying through. But even if there’s no actual magic involved, the flight requires a level of skill from our pilots that borders on wizardry. At various points, the wingtips of our Airbus A319—a 150-seat plane, weighing 35 tonnes—come so close to the hillsides that you can pick out individual kids standing on balconies, waving at us as we pass.

Often compared to Shangri-La, this tiny Himalayan kingdom, sandwiched between China and India, is home to the highest unclimbed mountain in the world.

“Only nine pilots in the world are qualified to fly into Paro,” my guide, Sonam, tells me after we’ve landed safely. It makes my arrival feel faintly miraculous, as if I’ve been granted access to a secret realm. It’s a sensation that only grows, with each day I spend exploring the Land of the Thunder Dragon.

There’s a lot about Bhutan that feels fantastical. Often compared to the fictional city of Shangri-La, this tiny Himalayan kingdom, sandwiched between China and India, is home to the highest unclimbed mountain in the world, and a national park dedicated to preserving the habitat of the yeti—just in case it exists. Bhutan only launched its first TV network as recently as 1999, and famously measures its development in Gross National Happiness, as opposed to GDP. Even their national animal, a bulbous-nosed buffalo called a Takin, looks like something out of a fantasy novel, or a hangover from the last ice age.

It takes about an hour to drive from Paro, the only place in the country flat enough to build a runway for modern jets, to Thimpu, Bhutan’s capital. It’s by far the country’s largest city, but still pretty small, with a population of just over 100,000. At one point we pass a white-gloved policeman directing traffic from a specially-built—and intricately decorated—box. “He is Bhutan’s only traffic light,” our driver Passang jokes.

After exploring the town and visiting several nearby Bhuddist temples, we set off for our first proper hike on day three. This is supposed to be a warm up for a longer, multi-day itinerary that will follow later in the week. But to my un-acclimatised lungs, used to living at sea level in London, it still feels like a significant effort. Thimphu itself sits at 2,320m (7,611ft)—higher than the highest ski resort village in the Alps—and the Phajoding Monastery that we’re hiking to is at 3,650m (11,975ft).

Despite the altitude, the swirling clouds and the occasional flecks of drizzle, both Sonam and Passang hike wearing their Gho—the traditional wraparound tunic that’s used for both smart and everyday occasions. Sonam makes the concession of donning a pair of trainers, but Passang completes the entire thing in his flat-soled brogues.

At the monastery—originally founded in the 12th Century—we get a tour from the abbot, Lama Namgay, who speaks near-perfect English. He introduces us to a young monk named Kencho, who volunteers to guide us further up the mountain to a remote “chorten,” or shrine, just above the high, Himalayan treeline—about 4,000m (13,123ft) above sea-level in this part of Bhutan.

As we climb up into the swirling mists, Kencho frequently has to wait for us to catch up. “They say the wind itself helps the monks and makes them faster,” explains Passang. Whatever it is, it’s not Kencho’s gear. In contrast to my Gore-Tex jacket and hiking boots, he’s wearing nothing more than a pair of flip-flops beneath his dark red robes.

Lunch back at Phajoding is a communal affair, consisting of curry-style stews, served with rice. One of these, a dish made of whole green chillies smothered in creamy cheese called ema datshi, crops up time and again during our treks, and fast becomes a favourite. I’m less keen on the customary method of making tea with tons of milk, and topped off with a heaped spoonful of homemade rice krispies. Another Bhutanese drink, which I’m served one evening while soaking in a traditional bath heated with stones, is even odder: it’s a cup of warm rice wine, mixed with yak butter and a spoonful of scrambled eggs.

They say the wind itself helps the monks and makes them faster...

Along with the incredible trekking and stunning Himalayan scenery, Bhutan’s otherworldliness is a huge part of its appeal. From little details like the Tibetan script used to write the Dzongkha language, to matters of life and death, like the “sky burial” sites we pass in the mountains, where the bodies of loved ones are offered up to vultures, there’s much that seems strange to my outsider’s eyes. But no custom is more unusual (nor, I would imagine, more remarked on by tourists) than the Bhutanese habit of painting penises on their houses.

The tradition, Sonam explains, stems from the cult of Drupka Kunley, a 15th century monk who founded the temple of Chimi Lakhang, in the Punakha valley, which we visit near the end of my trip. Kunley not only refused the normal vows of celibacy, but also “used his phallus to defeat a demon,” Sonam says. Today, couples hoping to conceive pray to him for fertility. And people in the Punakha valley—and indeed, all over Bhutan—paint penises on buildings to ward off evil spirits. These are not just scrawled bits of graffiti, but really graphic works of art. And they appear not just on homes, but on office blocks and public buildings.

If nothing else, these frequent dick pics serve as an illustration of the way that Buddhism underpins everything in Bhutan—including the legal system, schooling, and politics. But while religious traditions—including the quirky ones—run deep, this is not a country that’s stuck in the past.

The king, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, is believed to be the reincarnation of a Buddhist lama. But he’s also a millennial with an Instagram account, whose father—the much-revered fourth king—opted to give away power to create the current, constitutional system, where an elected prime minister calls most of the shots. “We call him the farsighted king,” explains Passang. “He’s my guy”.

It was also Wangchuck senior who introduced the idea of Gross National Happiness. While it sounds whimsical, it has had concrete impacts, ensuring that free education and healthcare are prioritised over economic growth—as is the health of the environment. Today, Bhutan boasts laws that would be the envy of even the most progressive European green parties. One states that 60 percent of its territory must remain forested, while another legally guarantees that it will always remain a carbon sink—absorbing more emissions than it produces.

“As Bhuddists, our leaders believe they have a duty not just to protect people, but all creatures,” explains Sonam. “And we must preserve the environment for the happiness of future generations too.”

Perhaps the most interesting upshot of Gross National Happiness—at least as far as visitors are concerned—are the rules designed to protect against the 21st century scourge of overtourism. There’s no cap on tourist numbers, but you can’t just rock up as a backpacker and hope to be allowed in. Visitors must book with a local tour company, and hire local guides for the duration of their stay. As well as their tour fees, all adult travellers must pay a tax of US$100 a day, known as the “Sustainable Development Fee.” By deliberately pricing many people out, the country is aiming to ensure that tourism remains a high value, but low volume activity.

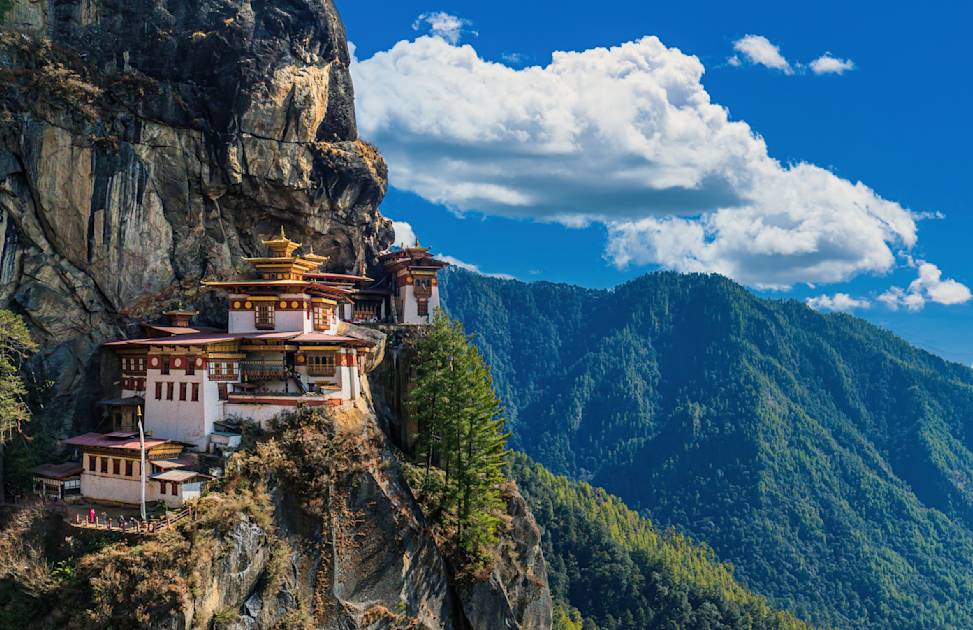

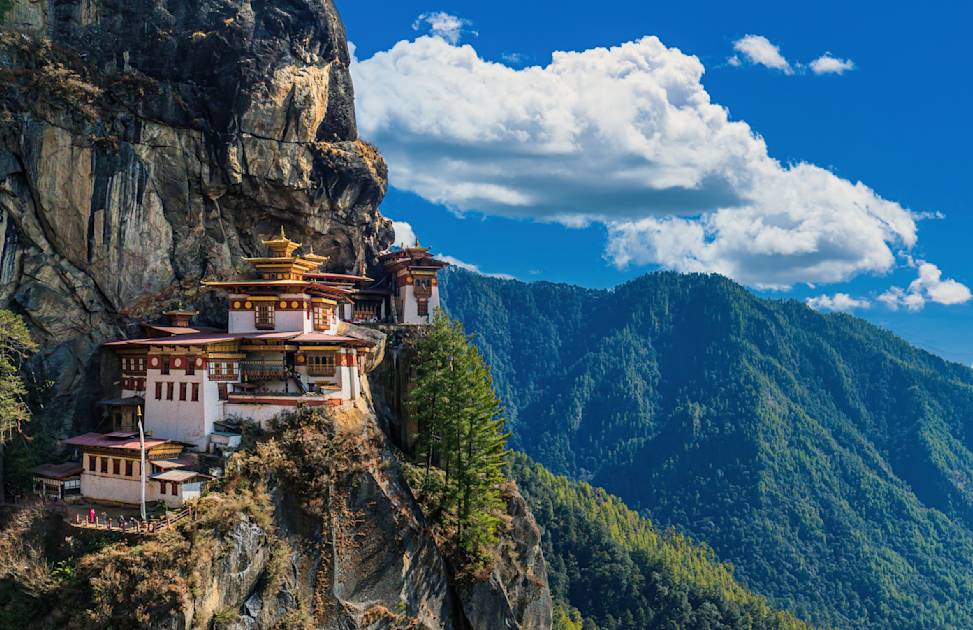

I see the upsides of this policy for myself when we visit the Tiger’s Nest Monastery, the UNESCO World Heritage Site that’s undoubtedly Bhutan’s most famous tourist destination. Built in the 17th century, it marks the cave where Guru Rinpoche, the father of Bhutanese Buddhism, spent several years meditating after arriving from Tibet on the back of a flying tiger.

This is a magical place. An Oz-like land that’s difficult to get to, but hard to leave behind.

It’s busier than anywhere else we’ve visited. But on both hiking up and then walking around the buildings, I find myself with more than enough space to stop and marvel at the architecture—not to mention the sheer audacity of building a monastery halfway up a cliff at 3,000m (9,842ft). Unlike many other UNESCO sites I’ve visited, it’s also perfectly possible to get a decent photo without having to queue, or crop out crowds of fellow visitors snapping selfies.

After a week in Bhutan—and countless explanations from my endlessly patient guides—I feel like I’m beginning to get the measure of the place. Some of the things that initially struck me as strange, like trying to quantify happiness and the anti-backpacker policy, now make perfect sense. Others, starting with those penis paintings, still leave me baffled. But that’s as it should be. After all, this is a magical place. An Oz-like land that’s difficult to get to, but hard to leave behind. They might not have flying houses, but they have plenty of temples that float above the clouds. What more could you hope for from Shangri-La?

Inspired? Trek the Druk Path and Trans Bhutan Trail on our new adventure!

Tristan Kennedy was a guest of the Bhutanese Ministry of Tourism.