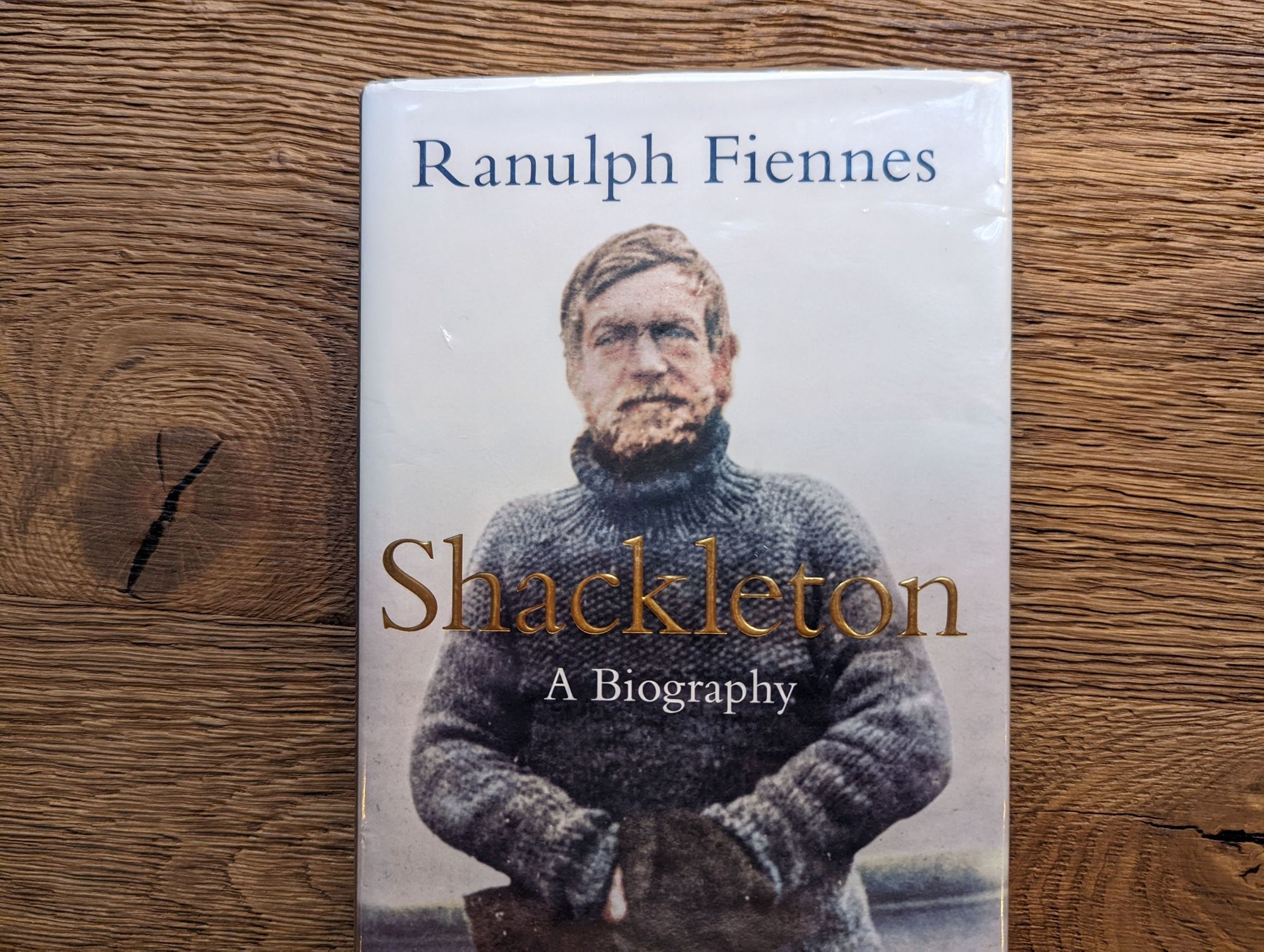

There have been many biographies of Sir Ernest Shackleton, but until now, “no previous Shackleton biographer has man-hauled a heavy sledge load through the great crevasse of icefields of the Beardmore Glacier, explored undiscovered icefields or walked a thousand miles on poisoned feet, hundreds of miles away from civilization.” So writes Sir Ranulph Fiennes in ‘Shackleton: A Biography’ - a book in which one of the most famous explorers of the modern age tells the story of one of the most famous Antarctic explorers of all time.

The biography tells the story of a young Irishman who through keen reading developed a passion for adventure. Leaving school at 16, Shackleton embarked on a journey of four years at sea on the Hoghton Tower, an old-fashioned, three-masted ship. We learn of his pursuit of his future wife Emily Dorman (and his possible infidelities), and how he excelled in social circles and as a public speaker. Above all, Shackleton yearned to make a name for himself, and so leapt at the chance to join Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s Discovery voyage.

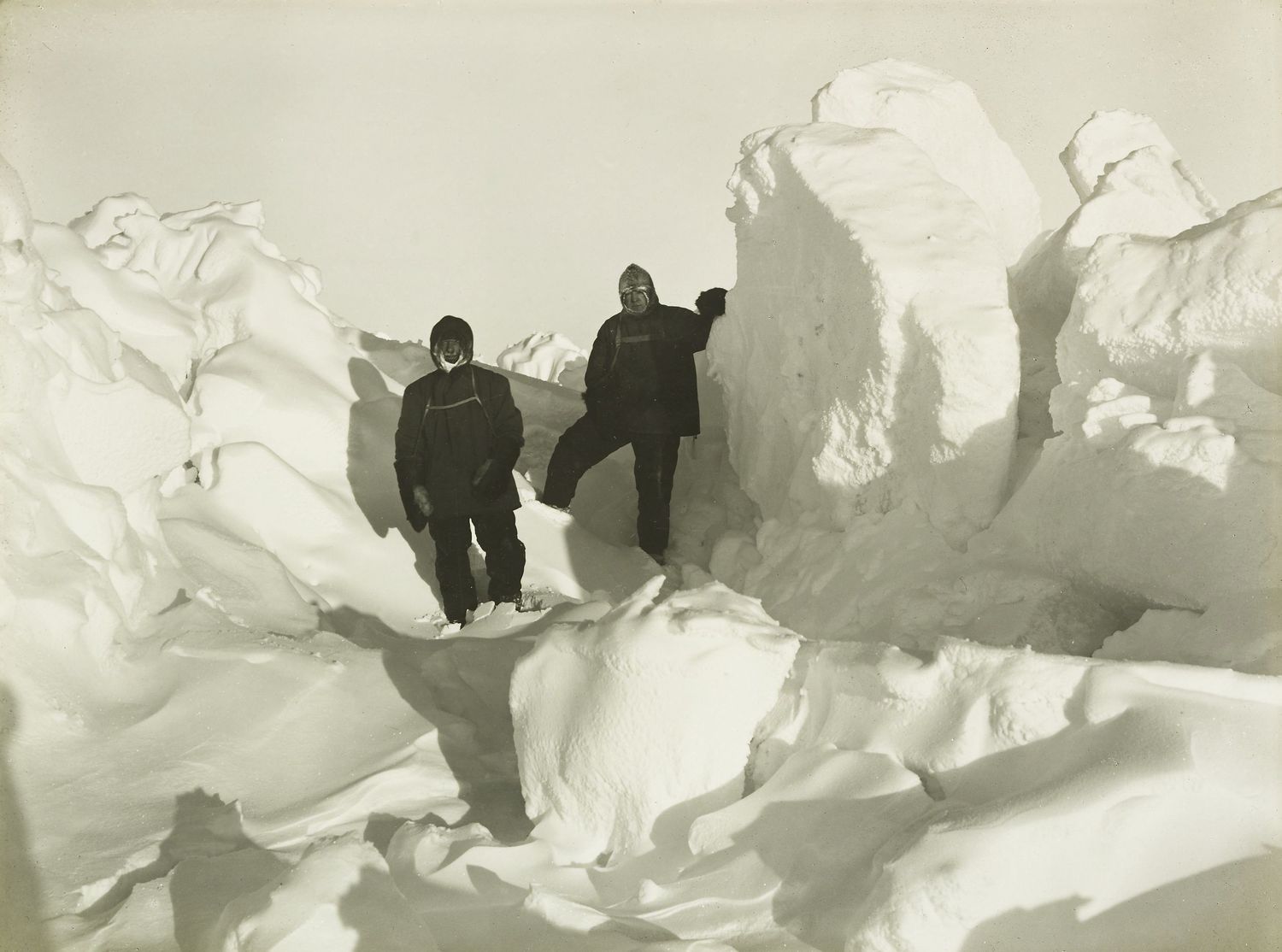

No previous Shackleton biographer has man-hauled a heavy sledge load through the great crevasse of icefields of the Beardmore Glacier

Scott would choose Shackleton as his third man (alongside Edward Wilson), to make an attempt on the South Pole itself. They beat the standing Farthest South record comfortably, but Scott would later denounce Shackleton as an “invalid”, and write “Shackleton has been anything but up to the mark”. Conditions were extreme and the group underprepared. Wilson had to “cocaine” his eyes for snowblindness, and Fiennes reflects on his own experiences in the Antarctic, where “the liquid in my eyes froze”. This is in addition to frostbite and scurvy.

By his own admission, Shackleton broke down on the return journey, but he was dismayed to be sent home early by Scott on their return to the Discovery. Scott said that this decision was motivated by Shackleton’s poor health, but on-board doctors believed there was no real necessity to send him home. It is possible that Shackleton was sent home to discredit him. Some believe that Scott was even in worse health. But Fiennes believes they were friends, and that Scott was indeed scared for Shackleton’s wellbeing. He does go on to write how “forced togetherness breeds dissension,” however, with various examples of his own.

Back home early, Shackleton was able to seize the narrative. He embarked on a lecture tour and - though it put him in great debt, which would haunt him for years - he would now lead a mission of his own to the South Pole on the Nimrod. Shackleton’s decision to go south again polarised him from the Royal Geographical Society, who believed that Scott (who was now back from Antarctica and planning another attempt on the pole) had more of a right.

Shackleton’s relationship with both Scott and Wilson was strained, and he was now leaving behind a wife in Emily who had just welcomed a second child. As Fiennes quotes, though: “The lure of the ice, it is a strange and powerful thing.” He goes on: “No matter all the discomfort and failure you might have endured, the urge to return is mesmeric. I’ve often described it as having the same pull as the one the smoker feels when trying to shun thoughts of tobacco.”

No matter all the discomfort and failure you might have endured, the urge to return is mesmeric.

Shackleton would ultimately set another Farthest South record, substantially beating that which was previously set by himself, Wilson and Captain Scott. They came just 112.2 miles (or 97.5 nautical miles, as Shackleton measured it) from the pole. The mission also included a first ascent of Mount Erebus, and scientists on board became the first to discover the Magnetic South.

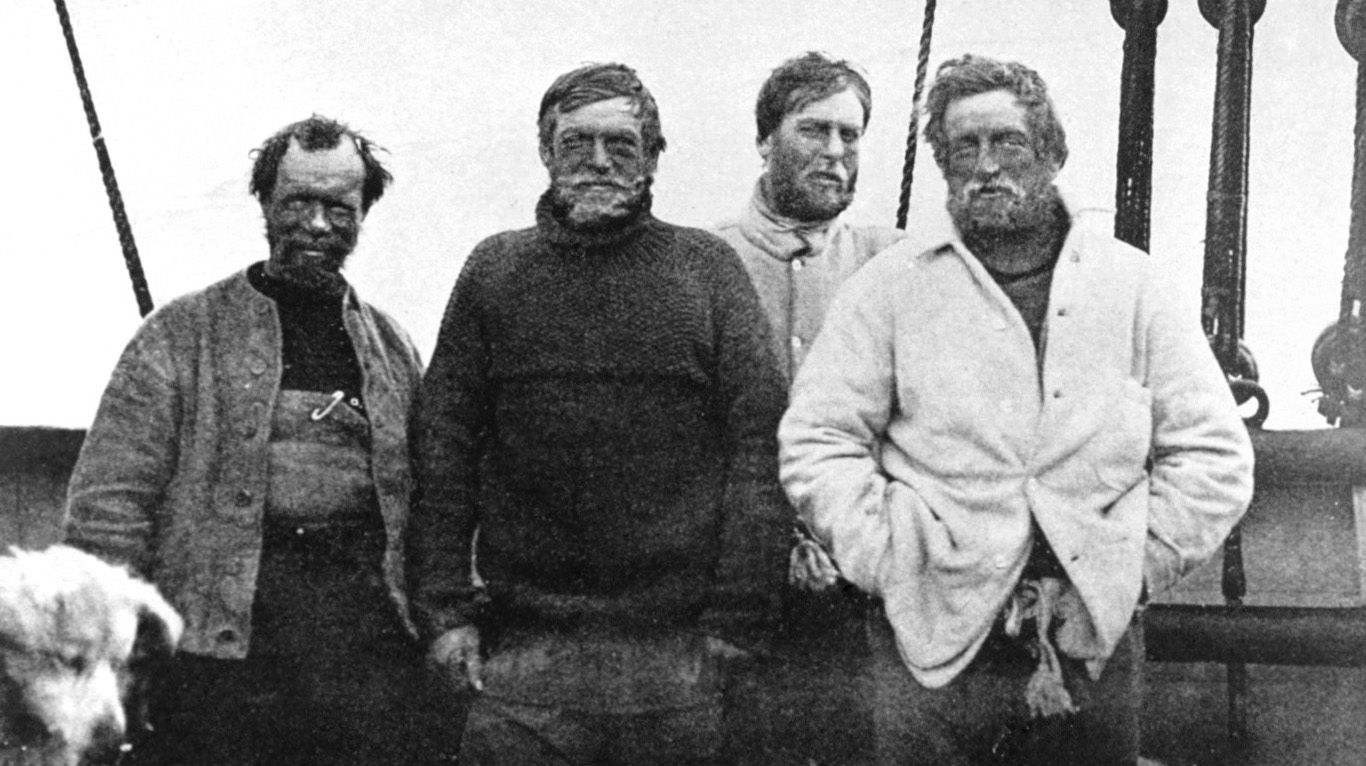

Through hellish conditions, Shackleton got himself and his three men back to the Nimrod, but Shackleton lost 24lbs in the process. Fiennes notes that in 1993, after 94 miles of Antarctic man-hauling, he himself lost 55lbs. He often wondered “what strain that might have put on my body, not least my heart, as in 2003 I suffered a massive heart attack at an airport and survived only thanks to a mobile defibrillator being immediately available”. Shackleton eventually died of a heart attack, and Fiennes writes of his Nimrod mission: “In my mind there is little doubt that he was now storing up troubles for the years to come.”

Shackleton returned a hero, and was knighted by the King. Roald Amundsen would soon reach the South Pole, and Captain Scott would follow - though he would perish in the process. Shackleton was not done with the ice, though. He set out to become the first to cross the entire Antarctic continent. Fiennes himself would later become the first to completely cross Antarctica on foot, in 1993. Shackleton's Endurance voyage, of course, turned to disaster - and he would instead be forced to lead one of the great survival stories of his time.

Shackleton's is the story of a man who struggled with a need to succeed, and despite his eventual celebrity, often found himself in debt. It is the story of a man who could not find his fulfilment whether at home or away - but though Shackleton never reached the South Pole, he did pave the way to it, and his leadership skills have become the stuff of legend.

Ranulph Fiennes quotes Sir Raymond Priestley, a polar contemporary of Shackleton, in the book. He said: “For scientific leadership, give me Scott. For swift and efficient travel, Amundsen. But when you are in a hopeless situation, when there seems to be no way out, get on your knees and pray for Shackleton.”

'Shackleton' is a well written, deeply-researched work on the great explorer. It provides little in the way of new material for those already familiar with the details of Shackleton’s story, but the main draw of this book is the parallels the author is able to draw to his own experiences in the Antarctic - and how these put Shackleton’s achievements into fitting perspective. For, as Fiennes writes in his introduction “to write about Hell, it certainly helps if you have been there.”

Inspired? Check out our full range of adventure holidays now!

This article contains affiliate links. Which basically means we make a little commission if you click through and buy something. It doesn’t cost you anything, and it just means we can do more good things in good places.