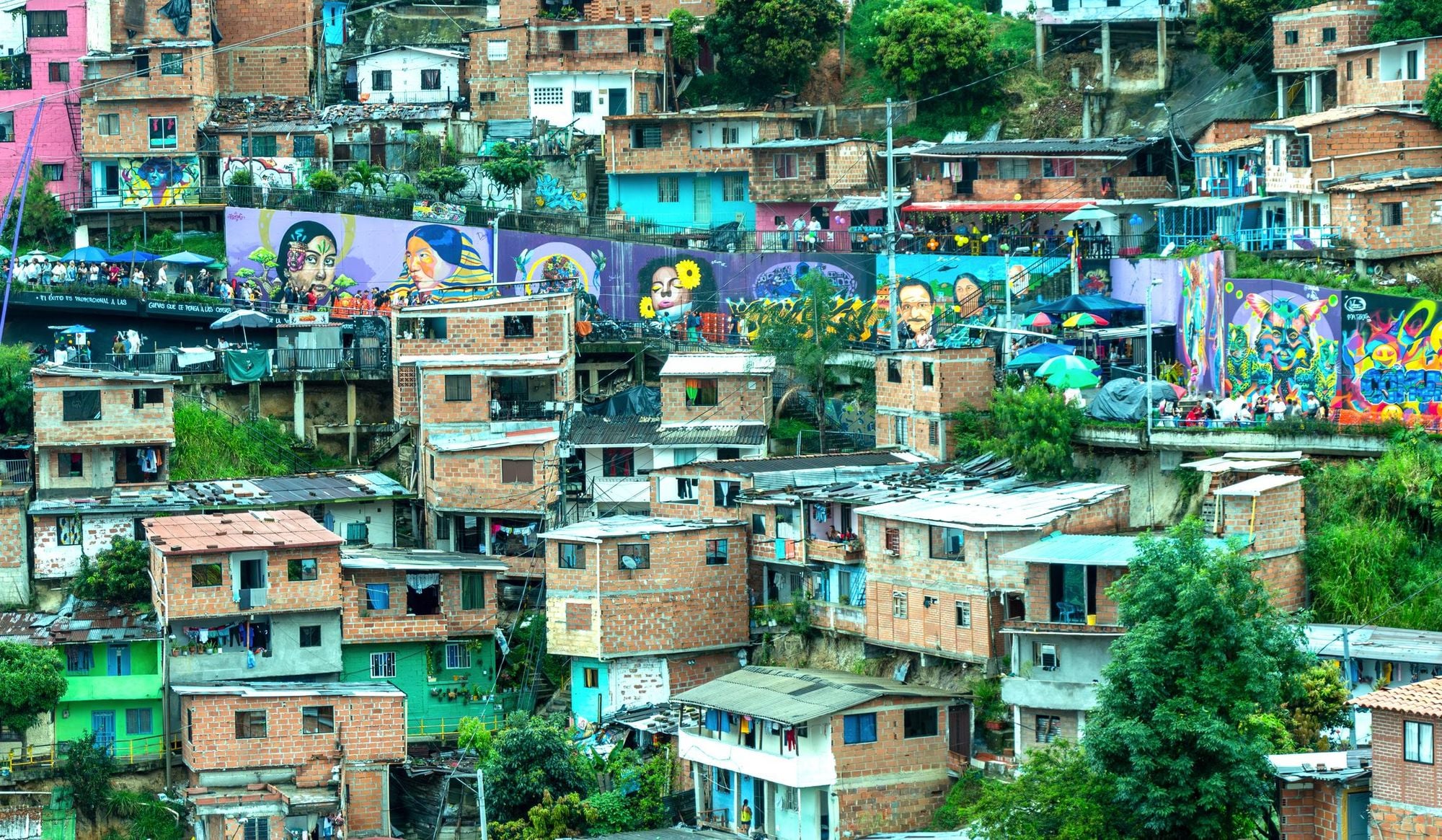

The colour-soaked walls of Comuna 13 tell a powerful story about this famous Colombian neighbourhood, which is stacked dramatically on the western hills of Medellín, looking out over the rest of the city.

The murals, painted by the local community, depict not only the turbulent, violent history of the area, but also the resilience, hope and strength which saw the neighbourhood emerge from it. The art - and the hip-hop and dancing that you see on the streets here now - helped to transform what was once one of the world's most dangerous districts into a global symbol of resurgence. Today, visitors explore in safety and with ease, thanks to the famous outdoor escalators - installed in 2011 - which made this once hard-to-reach hillside accessible.

The sheer volume of incoming tourists has now exceeded what the infrastructure can handle.

For years, Comuna 13 was one of the most powerful stories of urban transformation in Latin America, and it is still a story worth telling - but with global attention has come a new chapter, and it must be documented too.

Tourism is now a serious problem for locals on the streets of Comuna 13.

While visitors from around the world fuel the vibrant economy here, the sheer volume of incoming tourists has now exceeded what the infrastructure (including the outdoor escalators, designed for residents) can handle. That's why after conversations with our local partners, our itineraries will no longer visit Comuna 13 - and will now visit the up-and-coming Comuna 3 instead.

This isn’t a rejection of Comuna 13, and it’s not a denial of what the residents have achieved there against extraordinary odds. It is an acknowledgement of something which is harder to confront: that tourism, even when it begins with good intentions, can tip from empowerment into extraction.

Sometimes the most responsible decision a traveller can make is to step away.

From Terror to Transformation

To understand why overtourism in Comuna 13 is so significant, it is important to first understand the journey the community has been on in recent decades.

Strategically located on the western outskirts of Medellín, Comuna 13 became a part of the arms and drugs trafficking route in the 1980s and 90s, due to its strategic location. It was a natural, secluded corridor, away from government presence. During this time guerrilla groups, paramilitaries and drug traffickers all fought for control here. In October 2002, the violence culminated in Operación Orión. The largest urban offensive in the country's history, this was a military intervention that officially targeted armed groups but led to heavy civilian casualties and left deep scars among those living in the area, as well as establishing a lasting paramilitary presence in the Comuna.

When Medellín began to reimagine itself in the late 2000s, Comuna 13 became a focal point. Infrastructure arrived where abandonment had reigned. The most famous symbol was the outdoor escalators which climb the steep hills here - but this was the tip of the iceberg. Deeper transformation came from within.

A sense of pride emerged. Beautiful life models appeared: graffiti artists, breakdance dancers, young guides, and social leaders...

“This transformation emerged from the community itself, particularly from young people connected to rap and hip-hop culture,” says Ana Cristina Vélez Bunzl, who grew up in the area, and has worked as a guide there since 2014. Artists created spaces to tell their own story in their own voices.

“Tourism initially brought the possibility of feeling proud of where we come from,” says the guide. “Before, there was heavy stigmatisation: taxis would refuse to take you home; finding a job was extremely difficult. As things improved, a sense of pride emerged. Beautiful life models appeared: graffiti artists, breakdance dancers, young guides, and social leaders. Inspiration grew, and existing talent finally became visible.”

Groups like Casa Kolacho offered music, dance and art to the community, and murals began to document the loss and resistance that had taken place.

Slowly, outsiders started to visit - only in handfuls at first. In 2012, Simon Willis of Kagumu Adventures, partners of Much Better Adventures in Colombia, recalls: “you’d see three or four tourists, learning the story of resilience.” It felt meaningful. Tourism was having a positive impact. It brought income, pride and challenged Colombia’s narco-centred image. It showed a different Medellín.

The Tipping Point

Stories attract attention. Attention brings volume and before long, what was once a lived-in neighbourhood - Comuna 13 - gradually became a stage. Visitors began to arrive not on foot, but by the busload. Loudspeakers competed with one another for their attention. Stairs and walkways filled to the point where residents struggled to move through their streets, or go about their daily lives.

People dress up as Pablo Escobar and charge tourists for photos... the situation feels completely out of control.

“Some people couldn’t hear their telenovelas,” Simon recalls. “Others couldn’t get to hospital appointments because the escalators and stairways were blocked.”

Ana Cristina describes the change. “Noise levels have increased dramatically,” she says. “Trash has increased. Traffic is sometimes completely impossible. Informal construction has exploded - bars, restaurants, viewpoints, giant 3D figures for social media. Any crazy idea you can imagine has been done.”

Souvenirs celebrating Pablo Escobar - someone who, despite the belief of many visitors, did not have any direct ties to Comuna 13 - have become a contentious issue. “People dress up as Pablo Escobar and charge tourists for photos,” says Ana Cristina. “There is a Pablo Escobar museum. There are now souvenirs celebrating narcotrafficking. You can find tours that include drugs, sex workers, and parties. There are people who genuinely want to do things well and create something meaningful, but overall the situation feels completely out of control."

The guide adds: “It is important to say that Comuna 13 is a district of Medellín made up of many different neighborhoods. Some areas have not been deeply affected, but others - not only the touristic zone around the electric escalators, but also the surrounding neighborhoods - have undergone transformations.

“Financial capacity has clearly improved for many people, but at the same time everything has become much more expensive.”

For Ana Cristina, the emotional impact is profound. “When I go there now, I feel like an outsider in the place where I grew up,” she says. “The cultural loss is devastating. What tourists call Latin folklore is staged. It does not represent me.”

More troubling still is what gets lost beneath the noise: memory. Comuna 13 is recognised as a territory of state reparation, yet the history of the armed conflict risks being distorted or erased. “We are losing the true memory of the armed conflict and of what happened to us as a territory,” says Ana Cristina. “People no longer understand what happened, what was good, what was bad, and why. History has become blurred. Some visitors leave praising drug traffickers, seeing Comuna 13 as a place for partying, drugs and sex."

It is a narrative that ignores decades of abandonment felt by the residents.

“Tourism has now brought something I don’t even know how to name,” Ana Cristina admits. “Something that has translated into a new form of violence; imposing my noise, my disorder, my business, my trash, my parties, my fireworks onto others. No limits, no rules, no social fabric - only money.”

There is space in Comuna 3 to ask: what do we want tourism to be?

Particularly damning is the fact that children are pulled into the economy: begging, performing, competing for tips when they should be in school.

“At the same time, opportunists arrived,” says Ana Cristina. People from outside the area set up businesses and extract profit with little benefit to residents.

Ana Cristina recalls the moment she knew she had to stop bringing groups to Comuna 13. She was guiding in an area so loud she could barely speak to her group. There was heavy rain, and on an overcrowded escalator, tourists were blocking the top to take photos, oblivious to the people coming up behind.

“I felt panic,” she says. “Tourists are sometimes so distracted that they lose basic safety awareness and common sense.

"Where I used to live, there was a beautiful forest. It became impossible to enjoy it. When you walked there, you could hear a constant roaring from the escalators. Elderly people who cannot afford to move are desperate. They cannot rest.”

Choosing a Different Path

For Simon, conversations with local guides like Ana Cristina were decisive. “If something is not having a positive impact,” Willis says, “what’s the point? We have to be prepared to just say no.” But in this case, 'no' does not mean abandoning Medellín, nor the idea of community-led urban tourism. It meant asking a different question: where, and how, can this still be done responsibly?

The answer, for now, is in Comuna 3, also known as Manrique.

Less known, harder to reach and far from Instagram fame, Comuna 3 shares some similarities with Comuna 13’s past. It is home to many displaced families from across Colombia. Its walls also tell stories - beautiful murals depicting the history and resilience of the area. But crucially, tourism here is still small-scale.

“In Comuna 3, there is a real chance to set rules and frameworks early, before things spiral out of control,” Ana Cristina says. “Tourism was part of the project from the start, which meant that local authorities were involved early on through workshops, meetings and training processes. Local authorities were involved from the beginning. Some people are now close to graduating as professional guides.” There is space in Comuna 3 to ask: what do we want tourism to be?

“For me, truly ethical or sustainable tourism - whether in communities like these, or in any environment, urban or rural - is tourism that listens to and respects its surroundings.”

Visits are slower here, and more participatory. Travellers eat in local kitchens. Guests join reflection workshops, creating their own art alongside residents.

The experience is not about spectacle, but exchange. There are no escalators in this part of Medellín, meaning access is trickier. That is part of the protection.

What Responsible Tourism Really Means

Nobody is pretending that Comuna 3 is immune to the forces that overwhelmed Comuna 13. “Things change quickly,” Simon says. “We never know what’s going to happen in 10 years.”

That uncertainty is precisely why constant dialogue matters. Ethical tourism, as Ana Cristina defines it, is not a checklist but a relationship.

“It means asking: what does this place want? What are its limits?” she says. “Very often, tourists impose expectations. They want to use money to turn places into an amusement park, and sometimes communities - and operators - need to learn how to say no to those tourists.”

Responsible tourism requires a long-term commitment, not one-off visits. It is about clear rules, created with communities, not imposed on them. Transparency about where the money goes from such endeavours is crucial, and collective agreements that ensure tourism income supports shared needs.

It is about clear rules, created with communities, not imposed on them.

It also requires educating travellers on how to behave, what not to expect and why some things - like handing money to children - are not acceptable.

“You don’t go into a friend’s house and throw trash on the floor,” Ana Cristina says. “Tourism should work the same way.”

Comuna 13 will continue to attract visitors. Indeed, many residents depend on tourism income, and responsible local operators do still work in the area. This is not a call for boycotts or a moral judgement. It is, instead, an honest reckoning with the limits of tourism - and the responsibility within it.

Sometimes the most ethical choice is not to follow the crowds, but to step aside, listen, and support places that are still shaping their future on their own terms.

For us, for now, that means leaving Comuna 13 - with respect and gratitude - and walking into Comuna 3, where the story is quieter and still being written.

Inspired? Check out our adventure holidays in Colombia now!